Why Elections Matter

Keel Hunt recalls a time when bipartisan politics forged a better Tennessee

In Crossing the Aisle, Keel Hunt dives into the political history of Tennessee during the 1980s and 1990s, when Republicans and Democrats forged useful alliances that drove the state forward. “Anyone interested in creating jobs, building communities, solving problems, and moving forward with what Franklin Roosevelt once called ‘strong and active faith’ will find Hunt’s thoughtful explanation of the Tennessee story both illuminating and even inspirational,” writes historian Jon Meacham in the book’s foreword.

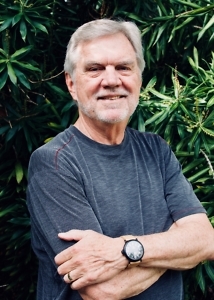

Keel Hunt is a columnist for the USA Today Network in Tennessee and the author of Coup: The Day the Democrats Ousted Their Governor. A former Special Assistant to Tennessee Governor Lamar Alexander, he is the founder of The Strategy Group, a public-affairs firm in Nashville. He answered questions from Chapter 16 via email:

Chapter 16: Your book argues that Tennessee underwent a transformative political era during the 1980s. What were the historical factors that drove this progress?

Keel Hunt: Some of the most important factors were national, not local. There were several powerful forces shaping politics in that period, actually beginning in the 1960s: the war in Vietnam and the anti-war movement at home, school desegregation and the violent reactions to it, the rise of television media, and campaign tactics that magnified divisive campaigns by driving “wedge issues.” All of that combined, across the South especially, to turn many conservative Democrats into new Republican voters.

By 1971 all three of Tennessee’s statewide elected officials were Republicans, but the legislature remained majority Democrat for years. Except for the eight years that Governor Ned McWherter was in office, Tennessee continued to have “divided government” throughout the 1990s. I call the 1980s and 1990s “the in-between time” because this was after much of the South had been so thoroughly Democrat for a hundred years but before we were a supermajority Republican as we are now.

What emerged in the in-between time were some extraordinary politicians in state government, by way of real competition between the political parties and strong individuals who ran for office. Almost all were center-right in their politics, with both a capacity to collaborate “across the aisle” and an understanding that it was necessary to get anything done.

Chapter 16: In the course of researching this book, you conducted 384 interviews, talking to just about every figure of political significance in the state, both then and now. As you kept conducting interviews, did your interpretation evolve? What shaped the stories you told?

Hunt: These twenty-five chapters each tell a story of something important that was accomplished through bipartisan cooperation. These range from the coming of the auto industry in the early 1980s to policy advances in education, health care, and transportation over the two decades. This is not another book about campaigns—but, more deeply, it is about why elections matter. For all the news media’s focus on campaigns and tricks to win office, the main thing always is what happens between elections. Elections matter because we always need policymakers who have that capacity to work with counterparts of the other party who also won their elections. This is the only way our society moves forward.

Chapter 16: A running theme in Crossing the Aisle is the partnership between Democrat Ned McWherter and Republican Lamar Alexander. What brought together these very different men?

Chapter 16: A running theme in Crossing the Aisle is the partnership between Democrat Ned McWherter and Republican Lamar Alexander. What brought together these very different men?

Hunt: They had gotten to know each other best on the afternoon of the “coup”—in January 1979. They and others concluded that Governor Ray Blanton must be removed from office in order to stop a scandal over prison pardons. In so doing, they developed a level of trust and mutual respect that endured over the eight following years. You’re correct—they were very different men, from different places and obviously opposing parties—but they worked well together, sometimes behind the scenes.

On the night after Alexander was sworn in three days ahead of schedule, which put Blanton out of power, a Nashville reporter asked McWherter why a Democrat had helped to swear in a Republican. McWherter cut him off, saying “First, I’m a Tennessean.” He told another reporter, “I’m going to [Alexander] because if he succeeds the state succeeds.”

Chapter 16: You highlight various engines of economic progress: the growth of FedEx in Memphis, the arrival of Nissan in Middle Tennessee, the revitalization of Chattanooga. What were the common politics behind these economic developments?

Hunt: All those companies were doing their own research, of course, and making their own decisions, but they uniformly found with Tennessee leaders of both parties a resolve to prepare the state for the future and work together in the process. These stories have mainly never been told until now.

Chapter 16: One fascinating story in this book is how the NFL came to Nashville—and did not come to Memphis. What are the political lessons in this tale?

Hunt: The same lessons as with the major corporate relocations and manufacturing developments: It was key for the outside decision-maker—like Bud Adams of Houston and his team—to see that mayors and governors were cooperating and committed in spite of coming from opposite political parties. This was especially true in the story of the Oilers/Titans.

Chapter 16: Tennessee is once again a state with one-party rule, this time led by Republicans. Is it even possible to recreate the dynamic, bipartisan political vision that drove the state’s progress in the 1980s and 1990s?

Hunt: Yes, of course it’s possible, and in fact it still happens. Generally speaking, we had good government in the ‘in-between time’ and we have it still—it’s just harder now because of so many external factors that have arisen in the public arena that affect how candidates win and leaders lead. Some of these are the rise of social media, the demise or shrinkage of so many newspapers, and the flood of money, including “dark money,” into political campaigns, making them much more divisive than before. Campaign finance rules have changed, not always for the better. All of that has made the job of the elected official—and certainly of the voters—much harder now.

Aram Goudsouzian chairs the history department at the University of Memphis. His most recent book is Down to the Crossroads: Civil Rights, Black Power, and the Meredith March Against Fear.