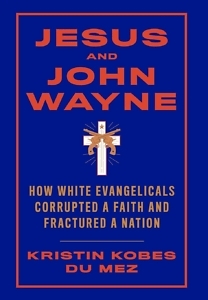

Wolves in Shepherd’s Clothing

Jesus and John Wayne considers the “evangelical cult of masculinity”

“Crushing truths perish by being acknowledged.” This hopeful aphorism from Albert Camus is one avenue for approaching the breathtakingly thorough and eye-rubbingly sad story Dr. Kristin Kobes Du Mez tells in Jesus and John Wayne: How White Evangelicals Corrupted a Faith and Fractured a Nation.

Du Mez, a professor of history at Calvin University, casts a critical eye upon a culture she knows well — the demographic group labeled “evangelicals” in polls and election cycles and its strange but alarmingly decisive bearing within local, state, and federal governments in the United States. Du Mez offers a granular take on her subject by isolating and analyzing an observable phenomenon in American life which, upon processing her study, readers are likely to see everywhere: “militantly patriarchal expressions” of a toxic faith which is, in turn, toxically political.

Du Mez, a professor of history at Calvin University, casts a critical eye upon a culture she knows well — the demographic group labeled “evangelicals” in polls and election cycles and its strange but alarmingly decisive bearing within local, state, and federal governments in the United States. Du Mez offers a granular take on her subject by isolating and analyzing an observable phenomenon in American life which, upon processing her study, readers are likely to see everywhere: “militantly patriarchal expressions” of a toxic faith which is, in turn, toxically political.

The title Jesus and John Wayne comes from a song of the same name from the Gaither Vocal Band. This attempted fusion of the peasant-philosopher Jesus of Nazareth with a popular cowboy icon both names and characterizes what Du Mez describes as “the evangelical cult of masculinity” and its accompanying patterns of misogyny and abuse. She begins with Theodore Roosevelt, whose image of “the man in the arena, whose face is marred by dust and sweat and blood” opened John Eldredge’s Wild at Heart: Discovering the Secret of a Man’s Soul, which Edgar Maddison Welch, popularly known as the Pizzagate gunman, claimed as his inspiration when he walked armed into Comet Ping Pong, hoping to save children kept in a dungeon by Democrats.

Compared to the pastors, pundits, presidents, and other personalities whose abusive speech and behavior Du Mez recounts in painstaking detail, Edgar Welch, who surrendered to police after firing a gun at a locked door and realizing his error, can seem like a marginal figure, but they all share a vision of sanctified aggression constantly reinforced through confusing the voice of God for the voice in their heads. She catalogues the harm by drawing on the public record of unscrupulous men, famous and not so famous, exercising inordinate power over other people’s lives by partnering with and covering for one another.

“I would rather see my four girls shot and die as little girls who have faith in God than leave them to die some years later as godless, faithless, soulless communists.” That’s Pat Boone in 1961 at a “freedom forum” hosted at Pepperdine College in Malibu, which included Ronald Reagan, Roy Rogers, and a televised luncheon with Barry Goldwater. From there, Du Mez invites us to recall Billy Graham’s defense in The New York Times of Lt. William Calley, convicted for the premeditated killing of unarmed South Vietnamese civilians in the My Lai massacre: “We have all had our My Lais in one way or another, perhaps not with guns, but we have hurt others with a thoughtless word, an arrogant act or a selfish deed.”

“I would rather see my four girls shot and die as little girls who have faith in God than leave them to die some years later as godless, faithless, soulless communists.” That’s Pat Boone in 1961 at a “freedom forum” hosted at Pepperdine College in Malibu, which included Ronald Reagan, Roy Rogers, and a televised luncheon with Barry Goldwater. From there, Du Mez invites us to recall Billy Graham’s defense in The New York Times of Lt. William Calley, convicted for the premeditated killing of unarmed South Vietnamese civilians in the My Lai massacre: “We have all had our My Lais in one way or another, perhaps not with guns, but we have hurt others with a thoughtless word, an arrogant act or a selfish deed.”

Amid the tales of victim blaming and powerful men enabling the bad behavior of other men under cover of darkness, dollars, and Bible verses, Du Mez reports the facts with a dry wit that serves to remind us how shockingly brazen professional God talkers can be: “Sometime in the mid-1980s, God had told Pat Robertson to run for president, according to Pat Robertson.”

We’re reminded that these men who rarely defer to anyone (apart from other men in the grip of the same abusive fantasies) write and pass laws. When allied with anonymous donors and elected officials, these fantasies become binding norms for people who’ve never read books by James Dobson, Mark Driscoll, or Tim Keller and who aren’t familiar with the ideology of complementarianism. Du Mez, however, has the goods on Hobby Lobby, The Gospel Coalition, and Lifeway Christian Resources. She offers a sober analysis of the threats we face from personalities and organizations that stand to profit off the cultivation of fear and a sense of embattlement.

By the time the story reaches 2015, we know feelingly that Trump didn’t start the fire. As Du Mez notes, “Evangelicals were looking for a protector, an aggressive, heroic, manly man, someone who wasn’t restrained by political correctness or feminine virtues, someone who would break the rules for the right cause.” Decades of normalized aggression, the habitual legitimation of the abusive man in a million households across the land, had already set the scene, and the former host of Celebrity Apprentice took to an extreme what others had only pursued halfway. Eighty-one percent of white evangelical voters were all in.

Even as revelations of sexual abuse in church organizations continue to surface, Du Mez observes that “Family Values” voters remain “curiously nonchalant about the dangers of unchecked power when … placed in the hands of a patriarch.” This book, however, persuasively exposes this lack of courage and conscience and functions as a clarion call.

David Dark is the author of five books, including The Possibility of America, Life’s Too Short to Pretend You’re Not Religious, and The Sacredness of Questioning Everything. He lives in Nashville and teaches at Belmont University and the Tennessee Prison for Women.