Wrestling for a Blessing

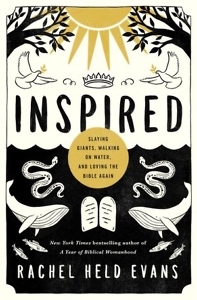

Bestselling Christian writer Rachel Held Evans re-examines the evangelical teachings of her youth

“In many ways, the Bible of my youth was set up to fail,” writes New York Times-bestselling memoirist Rachel Held Evans. “While American evangelicalism instilled in me a healthy love and respect for Scripture, many of its institutions taught me to expect something from the Bible it was never intended to deliver—namely, an internally consistent and self-evident worldview that provides clear, universal answers to all of life’s questions.” In her new book, Inspired: Slaying Giants, Walking on Water, and Loving the Bible Again, Evans attempts to reconcile the religious instruction she received as a child with the reality of life outside her faith community.

Evans grew up in Dayton, Tennessee, and she returned there as an adult after a newspaper stint in Chattanooga. Instructed in the evangelical Protestant tradition, her childhood faith was absolute and uncomplicated, and she was unprepared for the doubts that assailed her as she began to experience a more diverse culture:

Evans grew up in Dayton, Tennessee, and she returned there as an adult after a newspaper stint in Chattanooga. Instructed in the evangelical Protestant tradition, her childhood faith was absolute and uncomplicated, and she was unprepared for the doubts that assailed her as she began to experience a more diverse culture:

I grew up in a world where every pastor I knew was white and male, every theologian I admired came from Western cultures, every Bible study I attended was held in sprawling suburban homes. Rarely did I hear the words of Scripture spoken in an accent other than my own, and when it came time to color the faces of Moses, Mary, and Jesus in my coloring books, I reached for “peach.”

Evans ultimately left the denomination of her parents for a more progressive mainline tradition, but her discomfort with some of the Bible’s teachings continued to grow as she confronted people who use the Bible to justify hatred, violence, and every kind of oppression in society.

With Inspired, Evans tries to come to terms with her doubts and salvage her relationship with the Bible—and ultimately her faith. Drawing from the teachings of liberal scholars and interjecting humorous pop-culture references, Evans distills decades of biblical scholarship into a balanced and accessible overview of the ways in which the Bible instructs, surprises, horrifies, and delights. She begins each themed section with a short retelling of a Bible story. These are written in various creative styles, from “choose-your-own-adventure” to a particularly humorous screenplay version of Job in which God is represented by an angry Cafeteria Lady.

In her chapter on war stories, however, Evans gets serious. She wonders whether the Old Testament tales of God-sanctioned genocide and holy war are capable of being reinterpreted as something less offensive to modern sensibilities. How could a loving God deliver the Israelites from their brutal Egyptian oppressors one minute and call for the extermination of entire tribes of innocent people—every man, woman, and child—by the invading Hebrew army the next?

Longtime membership in a fundamentalist tradition gives Evans unique insight into the difficulty of getting a straight answer. “When I turned to pastors and professors for help,” she writes, “they urged me to set aside my objections, to simply trust that God is good and that the Bible’s war stories happened as told, for reasons beyond my comprehension.”

Longtime membership in a fundamentalist tradition gives Evans unique insight into the difficulty of getting a straight answer. “When I turned to pastors and professors for help,” she writes, “they urged me to set aside my objections, to simply trust that God is good and that the Bible’s war stories happened as told, for reasons beyond my comprehension.”

For her, this is the whole problem with fundamentalism: “It claims the heart is so corrupted by sin, it simply cannot be trusted to sort right from wrong, good from evil, divine from depraved,” she writes. “I’ve watched people get so entangled in this snare they contort into shapes unrecognizable.” Ultimately Evans takes comfort in her conviction that the life and death of Jesus is proof that “God would rather die by violence than commit it.”

Much of biblical interpretation depends upon motive—of those who wrote the Bible and those who wield it for their own purposes today. “The truth is,” she admits, “you can bend Scripture to say just about anything you want it to. You can bend it until it breaks.” She nevertheless finds inspiration within the Bible’s timeless stories, its colorful characters, and its realistic depictions of humanity—both its glory and its shame: “There are parts of the Bible that inspire, parts that perplex, and parts that leave you with an open wound,” she writes. “I’m still wrestling, and like Jacob, I will wrestle until I am blessed. God hasn’t let go of me yet.”

A graduate of Auburn University, Tina Chambers has worked as a technical editor at an engineering firm and as an editorial assistant at Peachtree Publishers, where she worked on books by Erskine Caldwell, Will Campbell, and Ferrol Sams, to name a few. She lives in Chattanooga.