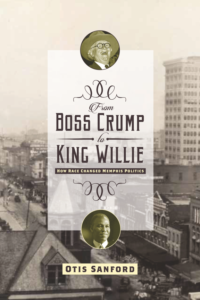

Writing for the City

Otis Sanford traces the twists and turns in Memphis politics

Every Sunday, readers of The Commercial Appeal in Memphis learn from Otis Sanford, who explains the local and national political scenes in a popular column. Now they can learn even more. Sanford’s first book, From Boss Crump to King Willie, explains the transformations in Memphis politics over the course of the twentieth century.

Otis Sanford is a former managing editor of The Commercial Appeal who now occupies the Hardin Chair of Excellence in Economic and Managerial Journalism at the University of Memphis. The longtime reporter also provides regular television commentary on Memphis politics. He answered questions via email for Chapter 16:

Chapter 16: In your day job, you are consistently analyzing the current political scene. What compelled you to take a historical approach for your first book?

Otis Sanford: I have always been fascinated by political history. And I have long wanted to connect the dots between E. H. Crump and Dr. Willie Herenton, the two most significant political figures in Memphis history. I was convinced that there was a great story to be told by linking those two. I was also convinced that most Memphians did not know the history behind some of the key people who were leaders in this city, and I wanted to tell that story.

Chapter 16: E.H. Crump controlled Memphis politics for a few generations, but it is difficult to assess his overall impact. Was he a force for good? How should we understand his legacy?

Sanford: In many ways, he was indeed a force for good. He brought order and organization to a rather dysfunctional city government, he insisted on maintaining a clean city, he improved the police and fire departments, and—perhaps more important—he listened to the concerns of African Americans when no one else in city leadership even bothered. He was also a generous guy who loved to throw parties for Memphians at his expense. On the other hand, he was vindictive, self-centered, and stubborn. If you crossed him, he came after you verbally and sometimes even physically. But there is no doubt that under Crump, Memphis grew to become a major metropolitan city with fine amenities.

Chapter 16: It is interesting to note the struggles for influence following Crump’s death in 1954. Who were the reform politicians trying to refashion Memphis government? To what extent were they successful?

Sanford: The major reformers during the latter part of Crump’s dominance were civic leader Edmund Orgill, attorney Lucius Burch, and newspaper editor Ed Meeman. They fought the Crump machine for years while pushing for a restructure of city government consisting of a council-manager form of government. They were unsuccessful during Crump’s lifetime. But after his death, Orgill became mayor at a time when the civil-rights movement was poised to take off in Memphis. He was seen as progressive, but he was not willing to advocate for school desegregation, and he only served one mayoral term, from 1955 to 1959.

It was not until the mid-1960s that true government reform occurred with the establishment of a mayor-council form of government. It allowed African Americans, for the first time, to win election to district council seats. Lucius Burch can be credited with trying to foster good race relations in Memphis in the late 1950s and early 60s, but the civil-rights movement was gaining steam faster than most of white Memphis could accept.

Chapter 16: Perhaps unsurprisingly for a Commercial Appeal columnist, your book often reflects upon the influence of the press. How did Memphis newspapers shape the city’s most important political debates, such as those over the 1968 Sanitation Strike?

Sanford: Memphis newspapers have always been powerful entities with an ability to sway public opinion and force political leaders to act a certain way. During the sanitation strike in 1968, both The Commercial Appeal and Memphis Press-Scimitar backed Mayor Henry Loeb, who refused to give in to any demand from the strikers. Both newspapers refused to recognize the strike as a civil-rights issue.

Sanford: Memphis newspapers have always been powerful entities with an ability to sway public opinion and force political leaders to act a certain way. During the sanitation strike in 1968, both The Commercial Appeal and Memphis Press-Scimitar backed Mayor Henry Loeb, who refused to give in to any demand from the strikers. Both newspapers refused to recognize the strike as a civil-rights issue.

The Commercial Appeal, in particular, strongly criticized Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.’s involvement. The criticism was extremely harsh after an initial march ended with violence. The Commercial Appeal editorials questioned Dr. King’s ability to lead a peaceful march in Memphis. Dr. King was determined to prove the paper wrong. He returned to lead a second march, but was assassinated before it could take place.

Chapter 16: Harold Ford Sr. plays a huge role in the history of Memphis politics. In what ways did he foster black progress?

Sanford: Harold Ford made history in 1974 when he was elected to Congress, representing Memphis. It was a stunning victory over an entrenched Republican incumbent. The African-American community viewed Ford’s win as validation and a testament to a long struggle for political inclusion, and Ford instantly became the most recognizable politician in Memphis. He also was great at constituent services, and that more than anything endeared him to the black community. For years, he ran a well-oiled politician machine, and white politicians clamored to get their names on the Ford ballot every election cycle. The Ford dynasty lasted more than thirty years. But it is no longer effective.

Chapter 16: It is common to hear that the 1991 election of Willie Herenton to mayor contributed to the city’s racial polarization, but your book tracks how white politicians circumvented black political power in the 1970s and 1980s. In other words, regarding Herenton’s election, did the white people of Memphis reap what they sowed?

Sanford: The main factor that led to Dr. Herenton’s election was white flight from the city that started with the assassination of Dr. King in 1968, continued with the annexation of Whitehaven in 1969, and really took off after the forced desegregation of city schools through busing in the early 1970s. As the white city population decreased and the black population increased, it was inevitable that the quest by African Americans to take the mayor’s office would become a reality.

Aram Goudsouzian chairs the history department at the University of Memphis. His most recent book is Down to the Crossroads: Civil Rights, Black Power, and the Meredith March Against Fear.