Creative Amnesia, or the Persistence of Magic

Novelist Steve Stern found his fictional world by searching for a lost Jewish tradition

So the author Stefan Zweig and Charles Steinmetz, the hunchbacked dwarf mathematician, were walking through Vienna at the end of the nineteenth century. As they passed a synagogue Zweig said, “I used to be a Jew,” to which Steinmetz replied, “I used to be a hunchback.”

I grew up wanting something I couldn’t name. I was raised in the Reform Jewish “tradition,” though the word here is gross hyperbole. The temple I attended as a kid in Memphis represented a variety of Judaism designed to be invisible, to blend indistinguishably with the Christ-haunted Southern landscape. We had no yarmelkes or prayer shawls, no bar or bat mitzvot; the rabbi wore ecclesiastical robes and preached before a choir loft appointed in the polished brass pipes of a sepulchral organ. Our hymnals retained only a smattering of Hebrew. There was nothing demonstratively Jewish in the liturgy, no fetishizing of the Torah scrolls, no conspicuous swaying at prayer; the congregation rose and sat obediently on cue. As a consequence, I was virtually untouched by tradition and had not even an awareness of its absence. Nevertheless, one Sunday, playing hooky from confirmation class, I went exploring the old red brick pile of our temple along with a couple of partners in crime.

2015 by the Center for Southern Folklore (from the Peiser Family Collection).jpg) We had no idea what we were looking for, though in retrospect I might call it mystery. Surely there was more to this allegedly hallowed environment with its austere sanctuary and freshly waxed Sunday-school corridors than met the eye. So we snuck through a door behind the altar and climbed a narrow flight of stairs into the choir loft. Behind the chairs at the back of the loft was a Hobbit-sized little door that was, surprisingly, unlocked, and opening it, we stooped to enter the musty darkness, holding our breaths. Greg Grinspan, who smoked, flicked his lighter, which illumined… well, not much of anything at all: some stacks of discarded prayerbooks, a bale of yellowed editions of The Hebrew Watchman, exposed rafters, and dust.

We had no idea what we were looking for, though in retrospect I might call it mystery. Surely there was more to this allegedly hallowed environment with its austere sanctuary and freshly waxed Sunday-school corridors than met the eye. So we snuck through a door behind the altar and climbed a narrow flight of stairs into the choir loft. Behind the chairs at the back of the loft was a Hobbit-sized little door that was, surprisingly, unlocked, and opening it, we stooped to enter the musty darkness, holding our breaths. Greg Grinspan, who smoked, flicked his lighter, which illumined… well, not much of anything at all: some stacks of discarded prayerbooks, a bale of yellowed editions of The Hebrew Watchman, exposed rafters, and dust.

Flash forward fifteen or so years: after living the life of my generation in various ports of call—a street theater in London, a commune in the Ozark Mountains of Arkansas—I’d fetched up again in what’s often referred to as the “backwater” of my native Memphis. I had little to show for my wanderings, having failed, among other things, to initiate a career for myself as a writer of fiction. My stories and novel had been roundly rejected by publishers, and when my agent admitted she was also, frankly, not so keen, I took as a kind of penance a job at a local folklore center, folklore being to my mind at least a poor relation to literature.

I was transcribing oral-history tapes, a tedious job that paid peanuts, but it introduced me to the history of a city that until then had seemed merely a good place for wishing you were somewhere else in. And to my great chagrin I discovered I was having a good time. The voices on the tapes were those of veteran old parties recalling the heyday of the fabled Beale Street, once the main street of African-American culture in the Mid-South. They described the raw vitality of the fleshpots and barrelhouses and its habitués: the root doctors, razor toters, diamond-toothed high-rollers and roustabouts, the copper-skinned dancers of the shimmy-she-wobble; they remembered the excursion boat and medicine-show bluesmen and the river before the TVA levees, when it flooded every spring. Then the bayous would back up, and the basin of Beale would become a temporary lagoon, across which the citizens would ferry themselves in lantern-hung skiffs.

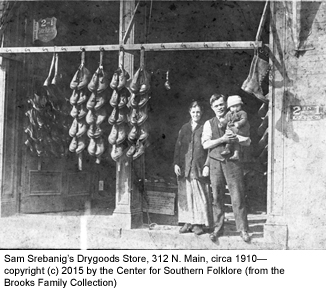

2015 by the Center for Southern Folklore (photograph courtesy of the Memphis-Shelby County Public Library).jpg) They ferried themselves over to a mercantile district owned and operated by a contingent of enterprising Jews. It was an odd symbiosis, black voices redn a bisl Yiddish, while fruity immigrant accents handled old clothes, dreambooks, and pomades. And for reasons I couldn’t quite comprehend the presence of those pawnbrokers and drygoods merchants in the midst of all that louche pageantry aroused my imagination. My enthusiasm was duly noted, as was the fact that I was local, worked cheap, and was of a distinctly Semitic cast myself; so I was anointed with the title of Ethnic Heritage Director and elevated to the task of researching the roots of Memphis Jewry—a project dubbed somewhat lamely “Lox and Grits.”

They ferried themselves over to a mercantile district owned and operated by a contingent of enterprising Jews. It was an odd symbiosis, black voices redn a bisl Yiddish, while fruity immigrant accents handled old clothes, dreambooks, and pomades. And for reasons I couldn’t quite comprehend the presence of those pawnbrokers and drygoods merchants in the midst of all that louche pageantry aroused my imagination. My enthusiasm was duly noted, as was the fact that I was local, worked cheap, and was of a distinctly Semitic cast myself; so I was anointed with the title of Ethnic Heritage Director and elevated to the task of researching the roots of Memphis Jewry—a project dubbed somewhat lamely “Lox and Grits.”

I was informed that the original locus of that community was a dilapidated quarter situated on and around North Main Street in downtown Memphis, an area I’d never heard of known as the Pinch. Once a vital East European enclave, it was barren now of all but a few vestiges of the defunct community—a warehouse with opaque glass windows that was formerly a shvitz bod, a Russian bath, a scrap-metal yard managed by three consecutive generations of the Blockman family, an abandoned synagogue whose final incarnation was as a nightclub featuring transvestite entertainment. The rest was a no-man’s land of condemned properties and weed-choked vacant lots.

But as I proceeded to ferret out the survivors of that community, interviewing seniors living now at a suburban remove from their blighted old neighborhood, North Main Street began gradually to reconstitute itself with its vest-pocket groceries and secondhand shops intact. Suddenly the air, as Martin Buber has it, was full of souls. Before my eyes the Pinch was repopulated with kosher butchers, piecework tailors, fishmongers, cigar-makers, haberdashers, and market wives dwelling above their businesses in cramped apartments, oven-like in the Memphis summers. To escape them the entire neighborhood would retire in a body to the Market Square Park, where they bedded down in their outdoor dormitory under the branches of a giant patriarch oak.

2015 by the Center for Southern Folklore (from the Peiser Family Collection) copy.jpg) I made the acquaintance of the ghosts of Mook Taubenblatt, the ward heeler; Reb Dubrovner, the ritual slaughterer, in the back of whose shop where the women sat flicking chickens there was a perpetual blizzard of feathers. I met No Legs Charlie Rosenbloom, the hot-headed amputee gambler, and the zaftig Widow Wolf who taught the greenhorns how to do the Black Bottom at the Neighborhood House, where later a young Elvis Presley would learn guitar. There was Eddie Kid Katz the glass-jawed welterweight contender and his manager, Nutty Iskowitz, proprietor of the Green Owl Café, where the socialists gathered; and Mr. and Mrs. Makowsky, the mom-and-pop bootleggers, with their colleague the flame-bearded Lazar der Royte, who appeared at his own arraignment—a hostage to piety—trussed in the leather thongs of his tefillin. There were the truant Talmud Torah scholars who threw catfish into the mikveh, the ritual bath, and the Galitzianer Hasids who, in their shtibl above Botwinik’s feed store, were rumored to pray in mid-air….

I made the acquaintance of the ghosts of Mook Taubenblatt, the ward heeler; Reb Dubrovner, the ritual slaughterer, in the back of whose shop where the women sat flicking chickens there was a perpetual blizzard of feathers. I met No Legs Charlie Rosenbloom, the hot-headed amputee gambler, and the zaftig Widow Wolf who taught the greenhorns how to do the Black Bottom at the Neighborhood House, where later a young Elvis Presley would learn guitar. There was Eddie Kid Katz the glass-jawed welterweight contender and his manager, Nutty Iskowitz, proprietor of the Green Owl Café, where the socialists gathered; and Mr. and Mrs. Makowsky, the mom-and-pop bootleggers, with their colleague the flame-bearded Lazar der Royte, who appeared at his own arraignment—a hostage to piety—trussed in the leather thongs of his tefillin. There were the truant Talmud Torah scholars who threw catfish into the mikveh, the ritual bath, and the Galitzianer Hasids who, in their shtibl above Botwinik’s feed store, were rumored to pray in mid-air….

In harvesting the memories of their sons and daughters, I collected as well—I was becoming insatiable—the traditions and superstitions they’d brought with them along with their samovars and featherbeds from the Old Country, what they called the Other Side. Thus did the vanished world of North Main Street begin to resurrect itself like some lost continent risen out of the sea.

That was anyway how I somewhat hysterically characterized the experience, as if my rediscovery of the Pinch had about it the taint of destiny. Around that time I also remembered that I wrote stories, though mine had previously inhabited fabricated landscapes where the consensus was they did not belong. The Pinch, with a vitality so absent from the arid subdivision in which I was raised—the Pinch, I decided, would be the fixed address where my stateless fictions could come home to roost. Then I wrote one set on North Main Street about an old one-eyed, peg-leg peddler so obstinate he refuses to die and as a result is abducted by Malach Hamovess, the Angel of Death, to Paradise while still alive. Clever, no? Though the story had about it a faint echo I felt drawn by curiosity to try and trace to its source—which, as I’d gleaned from my research, was the past. And the well of the past, as Thomas Mann put it, is very deep: “You might say it has no bottom.” So the echo grows louder the deeper you descend, until you realize that you had it backwards all along; your story is the echo’s farthest frequency and the immemorial past is the original source of the noise.

2015 by the Center for Southern Folklore (from the Fagie Schaffer Collection).jpg) In tales I’d been as ignorant of as I had been of the Pinch itself, I found Rabbi Pinchas of Koretz, another stubborn, deathless old man, who gulls the Angel of Death into admitting him into Paradise alive. Then there was Serah bat Asher, a cousin of Moses and prototype of the Wandering Jew, who endures from the exodus out of Egypt into the Middle Ages before she’s finally taken to the Upper Eden alive. There was the prophet Elijah, who ascends undying to heaven in a fiery chariot and returns in a bewildering variety of disguises to meddle for better or worse in human affairs; and Enoch, who receives only a passing mention in Genesis (“He walked with God and was not….”) but spawned an entire mystical literature. He was a cobbler who for his righteousness was translated to Paradise alive, where he became the archangel Metatron, who sits at God’s right hand. And those were the generations of my picayune story. Alright, then, maybe I wasn’t so clever after all, but voluptuously humbled, I consoled myself that I was in a tradition. It was the same tradition whose comet’s tail stretched behind the New World immigrants back to the shtetl and further back even to the Temple in Jerusalem and the desert where Abraham was seized with an iconoclastic fever.

In tales I’d been as ignorant of as I had been of the Pinch itself, I found Rabbi Pinchas of Koretz, another stubborn, deathless old man, who gulls the Angel of Death into admitting him into Paradise alive. Then there was Serah bat Asher, a cousin of Moses and prototype of the Wandering Jew, who endures from the exodus out of Egypt into the Middle Ages before she’s finally taken to the Upper Eden alive. There was the prophet Elijah, who ascends undying to heaven in a fiery chariot and returns in a bewildering variety of disguises to meddle for better or worse in human affairs; and Enoch, who receives only a passing mention in Genesis (“He walked with God and was not….”) but spawned an entire mystical literature. He was a cobbler who for his righteousness was translated to Paradise alive, where he became the archangel Metatron, who sits at God’s right hand. And those were the generations of my picayune story. Alright, then, maybe I wasn’t so clever after all, but voluptuously humbled, I consoled myself that I was in a tradition. It was the same tradition whose comet’s tail stretched behind the New World immigrants back to the shtetl and further back even to the Temple in Jerusalem and the desert where Abraham was seized with an iconoclastic fever.

I felt like Jonah having discovered that the fish that swallowed him had been swallowed in turn by a larger, and that one swallowed by an even larger, world without end.

Of course I didn’t find those tales on my own; I had the help of a maggid, a psychopomp or spirit guide, a figure that provides your safe passage between zones of the familiar and the uncharted extraordinary. Mine was the folklorist Howard Schwartz, who had snatched a clandestine literature out of the hands of the hidebound rabbis for whom those stories were embarrassing remnants from the childhood of the tribe. The stories in Schwartz’s anthologies, stories winnowed from a library of forgotten texts, made me wonder what else our rabbis were keeping secret, and as I was now in the business of researching roots, I decided to revisit my own.

I made the trip back to the old domed temple on Poplar Avenue, now a Baptist seminary. The Baptists were hospitable; greeting me like the prodigal son of a chosen people, they gave me the run of the place, which had hardly changed at all: the halls still reeking of floor wax, the sanctuary dense with its atmosphere of venerable boredom; but committed as I was to a thorough reconnoitering, I opened doors I’d never opened before, including one in the vestibule that led to a basement we’d missed—Randy Haspel, Greg Grinspan, and I—in our furtive adolescent investigations.

I made the trip back to the old domed temple on Poplar Avenue, now a Baptist seminary. The Baptists were hospitable; greeting me like the prodigal son of a chosen people, they gave me the run of the place, which had hardly changed at all: the halls still reeking of floor wax, the sanctuary dense with its atmosphere of venerable boredom; but committed as I was to a thorough reconnoitering, I opened doors I’d never opened before, including one in the vestibule that led to a basement we’d missed—Randy Haspel, Greg Grinspan, and I—in our furtive adolescent investigations.

I switched on a light and descended creaky wooden stairs into a dank, low-ceilinged area, where mops and buckets, folding tables and chairs were stored beside a dormant furnace. In a far corner was a dwarf door with a padlock hanging unlatched from its knob, which I turned; I opened the door, stooped, and entered, and in the lemony shaft that slanted from the caged windows, there he was: the Golem of Prague, that redoubtable brute molded from river clay by a sorcerer rabbi to do battle with the enemies of Israel, then retired, rendered inanimate this half a millennium after the letter aleph was erased from his dust-mantled brow. There were gilgulim, wandering spirits made visible now by the luster of their cobweb gowns called malbushim, soul garments in their washed-out rainbow hues; and the lamed vov tzadikim, the thirty-six righteous men for whose sake the Lord refrains from destroying the earth, sitting on their ragged haunches like fugitives in a station of the Underground Railroad. (One of them kept blurting off-color jokes, evidence that a dybbuk, or malevolent spirit, had taken up residence in his breast.) There was Lilith, Adam’s first wife, the outcast demoness, losing her looks since she’d left off fornicating with sleeping bachelors; and the Shekhinah herself, God’s own shimmering better half, now a rueful agudah, or abandoned wife. Even the Angel of Death was among them in his flea-bitten obsolescence, his services trumped by the much more able offices of men. It was a gathering of all the back-numbered phenomena the rabbis had kept hidden for a century or more, lest they compromise our very sensible religion in the eyes of the goyim.

Or so I imagined.

After the destruction of the Second Temple and the banishment of the Jews in 70 AD from Jerusalem, their sages were much preoccupied with how to sustain a religion in exile. They wisely conceived a canonical body of laws that would serve as a kind of armature of ethical living for their people. Those laws, distilled from Torah and comprising an inextricable appendix to it, would become the foundation of the religion ever after, and the books of Torah, Mishnah, and Talmud would come to be regarded altogether as a single evolving volume. Later the Muslim caliphate would label the Jews that resided among them the People of the Book, as if the Book were itself a national entity wherein they dwelled. To us the designation is metaphorical, but in the collective mind of the Jews of that time the conceit was the literal definition of their circumstance.

2015 by the Center for Southern Folklore (from the Peiser Family Collection).jpg) Surrounded as they were by hostile hosts throughout the long centuries of Diaspora, the Jews embraced the Book as the emblem of their identity; its laws were the framework upon which were hung the fundamentals of ritual, culture, and heritage. There was for them no secular literature, no literature at all beyond the Torah (the Five Books of Moses) and its commentaries—as why should there be? The very idea of a literature outside of the sanctified canon was heretical; the Book was received from God and therefore definitive. It was a formidable book; it had to be to contain the essence of an entire people, and its language, though often rhetorical and hair-splittingly legalistic, could also be seductively lyrical and enigmatic. Its words, being holy, had curious properties: they had texture, dimension, and plasticity; the Book was a web of words that gave the rabbis who abided within its pages—constrained though they were by moral and clerical concerns—a certain acrobatic buoyancy.

Surrounded as they were by hostile hosts throughout the long centuries of Diaspora, the Jews embraced the Book as the emblem of their identity; its laws were the framework upon which were hung the fundamentals of ritual, culture, and heritage. There was for them no secular literature, no literature at all beyond the Torah (the Five Books of Moses) and its commentaries—as why should there be? The very idea of a literature outside of the sanctified canon was heretical; the Book was received from God and therefore definitive. It was a formidable book; it had to be to contain the essence of an entire people, and its language, though often rhetorical and hair-splittingly legalistic, could also be seductively lyrical and enigmatic. Its words, being holy, had curious properties: they had texture, dimension, and plasticity; the Book was a web of words that gave the rabbis who abided within its pages—constrained though they were by moral and clerical concerns—a certain acrobatic buoyancy.

As the saying goes, “The Torah is a tree of life for those who cling to it,” and sometimes a trampoline. Encountering, for example, the conundrum in Genesis where God creates light on the first day and the sun not until the fourth, the rabbis, bouncing into some rarefied state of consciousness, conceived the Tzohar. This was the jewel in which God stored the primordial light that preceded the sun, which Adam and Eve took with them when they were expelled from the Garden to remind them of all they had lost. It’s the same stone that turns up as a window in Noah’s ark, as a gem in the cup that enables Joseph to interpret dreams, as the sacred light that will be restored when Messiah comes. In the words of the visionary Hasid Nachman of Bratslav:

Every story has something that is concealed. What is concealed is the hidden light. The Book of Genesis says God created light on the first day, the sun on the fourth. What light existed before the sun? Tradition says this was the spiritual light, and God hid it for future use. Where was it hidden? In the stories of the Torah.

The Torah was the resilient tissue of faith from which the rabbis catapulted themselves into wild imaginings, and the net to which they always returned. In this they resembled the Adne Sadeh, the midrashic creature created before man, its navel cord—which was attached to the earth—determining its range of movement. Thus were the old rabbis tethered to holy writ, though theirs was an elastic connection like a bungee cord.

2015 by the Center for Southern Folklore (from the Peiser Family Collection) copy.jpg) The Jewish mystical tradition that developed throughout the Middle Ages and culminated in Moses de Leon’s Book of Radiance maintained that the universe was created from the twenty-two letters of the Hebrew alphabet. It was after all fitting that a people who lived in a book should understand that theirs was a world made of words, a story told by God. It was not always a pleasant story, was often nasty, brutish, and hedged about by enemies—Crusaders, Inquisitors, Cossacks bent on the oppression and conversion—if not wholesale annihilation—of the Jews in their midst. It was a story characterized for most by demoralizing poverty, bracketed by unjust and byzantine laws, at least when viewed exclusively from the vantage of time.

The Jewish mystical tradition that developed throughout the Middle Ages and culminated in Moses de Leon’s Book of Radiance maintained that the universe was created from the twenty-two letters of the Hebrew alphabet. It was after all fitting that a people who lived in a book should understand that theirs was a world made of words, a story told by God. It was not always a pleasant story, was often nasty, brutish, and hedged about by enemies—Crusaders, Inquisitors, Cossacks bent on the oppression and conversion—if not wholesale annihilation—of the Jews in their midst. It was a story characterized for most by demoralizing poverty, bracketed by unjust and byzantine laws, at least when viewed exclusively from the vantage of time.

But the Book afforded another vantage, a timeless mandate that held dominion over whatever misery imbued the quotidian world. In the shtetls of the Russian Pale of Settlement, to which the better part of Eastern Europe’s Jews were confined, the blacksmiths, shopkeepers, midwives, tinkers, matchmakers, and fools suffered disease and deprivation, constant menace and nightmares run amok in broad daylight; but they also had available to them, coincidentally, a space wherein the Red Sea still remained parted and every dawn was the one in which Jacob refused to let go of the angel until he received the blessing he was entitled to.

In his tumbledown landscape the pious tinsmith shooed from the outhouse the pesky demons that liked to congregate there, while household imps—shretelekh, lantekh, and kapelyushniklim—assisted the balebosteh, the tinsmith’s exemplary wife, at her chores. A horny yeshiva scholar in his beit hamidrash, the ramshackle study house, might be enticed by the temptress Lailah to step through the rabbi’s pier glass into the infernal left-hand kingdom of Sitra Achra. (That’s where the creatures resided that the Lord made in such a hurry on the Friday evening of Creation that He neglected to give them bodily forms.) A bride beneath her wedding canopy, forced into an arranged marriage, might speak in the disembodied voice of the lover who killed himself for want of her hand. A water-carrier, picking his way through the porous atmosphere of the Jewish street among a pack of reincarnated souls (the adulteress become a donkey, the cruel landlord a bumblebee), might spy a rusalka, a mermaid, sunning herself on the river rock where the washerwomen wrung out their clothes. Meanwhile, Shifra Leah’s incorrigible son, Zaynvil, was said to have stolen the Shem ha-Mephorash, the Ineffable Name of God, from his rebbe. He took a knife and made an incision in the sole of his foot, inserted the Name and sewed it shut, then straightaway sprouted wings.

2015 by the Center for Southern Folklore (from the Peiser Family Collection).jpg) If myth takes place in a neverness beyond time, folklore occupies a more domestic environment, whose boundaries are nonetheless extended beyond the common conventions of the real. Where myth takes for granted the impossible, folklore subverts the possible. Myth inhabits its own realm outside of history, while folklore bridges the distance between history and myth, its denizens commuting to and fro. As a consequence the beggar that knocked at your door in Drogobych to entreat a Shabbos meal might be the prophet Elijah or even Messiah himself, finally done tarrying in his palace called the Bird’s Nest.

If myth takes place in a neverness beyond time, folklore occupies a more domestic environment, whose boundaries are nonetheless extended beyond the common conventions of the real. Where myth takes for granted the impossible, folklore subverts the possible. Myth inhabits its own realm outside of history, while folklore bridges the distance between history and myth, its denizens commuting to and fro. As a consequence the beggar that knocked at your door in Drogobych to entreat a Shabbos meal might be the prophet Elijah or even Messiah himself, finally done tarrying in his palace called the Bird’s Nest.

Of course, negotiating between the opposing poles of time and timelessness, logos and mythos, could be a precarious navigation, but for their part the shtetl folk managed it with a studied dexterity, even as they practiced the death-defying art of survival. They had in any case the Book for a map, and the map sometimes supplanted the world. A topographical map, its hills and valleys were fretted with veins of wondrous stories—midrash, aggadot, and later the hagiographic tales of the Hasidim—that the rabbis had quarried in their delvings into Scripture. For the rabbis were as deft at spelunking as they were at taking flight.

That was how things stood with the Diaspora Jews until around the end of the nineteenth century. The Enlightenment was late in coming to Eastern Europe, but it arrived with a vengeance. Modernity, a phenomenon the Jews called Haskalah, invaded even the remotest communities, and under the influence of secular education and the advance of long deferred political gains, assimilation at last became possible and tradition began to retreat. At the very moment when Freud and his disciples were introducing the West to the lost province of the human psyche, the historians were busy sweeping all evidence of Jewish superstition and folk belief under the rug.

2015 by the Center for Southern Folklore (from the Halpern Collection).jpg) The project of pioneer historiographers such as Heinrich Graetz and Simon Dubnow was to present a rational and somewhat sanitized version of Judaism to the rest of the world, a religion divested of its “medieval” and “exotic” elements. Meanwhile new ideologies—Marxism, Zionism—were being embraced by the young with a messianic ardor previously reserved for religion itself. Granted, there were those who mounted last-ditch salvaging campaigns—Louis Ginzberg in his Legends of the Jews, Berdyczewski’s Mimekor Israel, Bialik and Raznitsky’s Sefer Ha-Aggadah—in an effort to rescue the folktales and fables from their consignment to oblivion; there was also a burgeoning Yiddish literature, rich and diverse, that provided a temporary haven for golems (see I.L. Peretz), dybbuks (see A. Ansky and I.B. Singer), and wandering souls (see Mendele Mocher Seforim). But in the main the end of the Jews’ disenfranchisement from the national polities they inhabited, however qualified their emancipation might be, marked the beginning of their exile from the Book.

The project of pioneer historiographers such as Heinrich Graetz and Simon Dubnow was to present a rational and somewhat sanitized version of Judaism to the rest of the world, a religion divested of its “medieval” and “exotic” elements. Meanwhile new ideologies—Marxism, Zionism—were being embraced by the young with a messianic ardor previously reserved for religion itself. Granted, there were those who mounted last-ditch salvaging campaigns—Louis Ginzberg in his Legends of the Jews, Berdyczewski’s Mimekor Israel, Bialik and Raznitsky’s Sefer Ha-Aggadah—in an effort to rescue the folktales and fables from their consignment to oblivion; there was also a burgeoning Yiddish literature, rich and diverse, that provided a temporary haven for golems (see I.L. Peretz), dybbuks (see A. Ansky and I.B. Singer), and wandering souls (see Mendele Mocher Seforim). But in the main the end of the Jews’ disenfranchisement from the national polities they inhabited, however qualified their emancipation might be, marked the beginning of their exile from the Book.

The banishment was gradual at first. But ultimately those whose lives remained circumscribed by the Torah and its commentaries were betrayed by the nationalities that claimed to include them—then largely destroyed along with the decimation of their texts. Even their tongue, their mameloshen, the homely Yiddish that was the final refuge of the old folk wisdom, was excised.

What was left in the wake of the slaughter was a world like a scab, with here and there some relic of the Book poking through its surface: Jacob’s Ladder and Aaron’s rod reduced to cinders; the Tree of Life itself, once the spine of the universe in the discourse of mystic Kabbalah, become a scrawny leafless scrub. Think of the tree beside which Vladimir and Estragon in Samuel Beckett’s Godot await a personage that never comes. Another rendition of that fruitless anticipation is captured in Kafka’s parable of the man from the country, who waits his entire life to be admitted to the Palace of the Law only to expire outside the door intended only for him.

2015 by the Center for Southern Folklore (from the Peiser Family Collection).jpg) Much of the most indelible literature of the last century, in the middle of which my aging generation was born, could be characterized as an elegy for our seemingly terminal alienation from the Law. (For Law read God, truth, meaning, each other, ourselves; you name it, we were alienated from it.) And wouldn’t it have been an idiotic betrayal of our existential moment to make believe it could be redeemed by fantasy? Like the Jews in their exile from the Book, the most passionate of our literary artists seemed sentenced to mourn, albeit with grace, their banishment to a desert of attenuated reality, a place proof against the sublime consciousness the old rabbis achieved in their raptures.

Much of the most indelible literature of the last century, in the middle of which my aging generation was born, could be characterized as an elegy for our seemingly terminal alienation from the Law. (For Law read God, truth, meaning, each other, ourselves; you name it, we were alienated from it.) And wouldn’t it have been an idiotic betrayal of our existential moment to make believe it could be redeemed by fantasy? Like the Jews in their exile from the Book, the most passionate of our literary artists seemed sentenced to mourn, albeit with grace, their banishment to a desert of attenuated reality, a place proof against the sublime consciousness the old rabbis achieved in their raptures.

And so the project of jettisoning magic from the Jewish tradition, begun by the zealots of Haskalah, was completed and then some during the Second World War. I would submit that a sizable portion of what makes us human was also forfeited during the Holocaust; the Shoah completed the process begun by the fall of Adam. But if that’s really the case, then conscience might compel us to return to the scene of the crime to retrieve what was lost—though to confront that horror in all its magnitude is a task requiring more chutzpah than is available in our unheroic age; it’s an endeavor that has its echo in the kabbalistic concept of tikkun, the healing of the rift between heaven and earth. That theory, conceived by the wizardly Isaac Luria in sixteenth-century Safed, has it that God, in creating the cosmos, breathed overmuch divinity into the vessels that contained it, fragile vessels that burst from an excess of splendor, scattering sparks throughout the world. It was therefore the responsibility of mankind to gather those holy sparks, prying them loose from the husks of evil that surround them, and restore them to the Godhead, thus repairing a broken world. That is, if you could find the Godhead.

, principal of The Smith School, 1918—copyright (c) 2015 by the Center for Southern Folklore (from the Lolly Dan Collection).jpg) The Old World synagogues had rooms set aside for storing outworn Torahs and holy texts. Often those scrolls and mildewed volumes moldered in their repositories, called genizahs, awaiting a proper burial that seldom occurred. My synagogue had no such repository, unless you allow me my basement hallucination with its supernatural assemblage, waiting—not unlike Vladimir and Estragon and Kafka’s man from the country—for their eventual redemption. I could pretend that for them the story ended happily: when, in an intrepid rescue operation, I, a Harriet Tubman of the archetypes, liberated the whole fantastical menagerie and resettled them in attractive new homes, in tales of my own construction, where they reassumed the powers that had atrophied during their long confinement.

The Old World synagogues had rooms set aside for storing outworn Torahs and holy texts. Often those scrolls and mildewed volumes moldered in their repositories, called genizahs, awaiting a proper burial that seldom occurred. My synagogue had no such repository, unless you allow me my basement hallucination with its supernatural assemblage, waiting—not unlike Vladimir and Estragon and Kafka’s man from the country—for their eventual redemption. I could pretend that for them the story ended happily: when, in an intrepid rescue operation, I, a Harriet Tubman of the archetypes, liberated the whole fantastical menagerie and resettled them in attractive new homes, in tales of my own construction, where they reassumed the powers that had atrophied during their long confinement.

But if I’m honest, I have to admit that they never fully adjusted to those artificial environments, try as I might to design them according to the blueprints of their original milieu; and in their displacement the creatures appeared to me (and sundry book reviewers) as desolate as Frankenstein’s monster on his solitary ice floe. Maybe I should have left well enough alone, left those quaint figments of outmoded lore to gather dust in their funk hole under Temple Israel—where, in truth, they were less like fugitives en route from captivity than passengers in the hold of the SS St Louis, denied entry to the ports of all nations and returned to Germany to perish in Hitler’s gas chambers.

In an old Hasidic parable the Baal Shem Tov, founder of the movement, would go to a place in the forest, light a fire, say a prayer, and achieve enlightenment. His nephew followed suit: entered the forest, lit the fire, and found he’d forgotten the prayer, but he decided it was enough just to be there beside those embers in that place. The nephew’s daughter also went into the forest only to realize she’d forgotten the prayer and had no idea how to light a fire, but again just to be in that place in the forest was enough. The nephew’s daughter’s son, however, can’t even find his way to the forest, never mind light a fire and recall a long-forgotten prayer, but he remembers the story of the forest, the fire, and the prayer, and that in itself is sufficient.

2015 by the Center for Southern Folklore (from the Peiser Family Collection).jpg) My fear is that my generation and its successors no longer even remember the story—though perhaps our amnesia is a blessing in disguise? In another old legend the Angel of Forgetfulness tweaks the newborn under the nose at birth to erase its knowledge of Paradise, a knowledge with which it’s assumed that life on earth would be intolerable. Then we’re fortunate to be spared the pain of remembering. But hasn’t that forgetfulness infected our post-natal consciousness as well, so that the crumbs (or sparks) of ritual, culture, and heritage that led back to their luminous source in the Book seem scattered beyond recovery? Leaving us in a Diaspora of the spirit, where the rabbis—once so adept at kfitzat ha-derekh, the enchanted seven-league Leaping of the Way—have lost their ability to bounce and delve.

My fear is that my generation and its successors no longer even remember the story—though perhaps our amnesia is a blessing in disguise? In another old legend the Angel of Forgetfulness tweaks the newborn under the nose at birth to erase its knowledge of Paradise, a knowledge with which it’s assumed that life on earth would be intolerable. Then we’re fortunate to be spared the pain of remembering. But hasn’t that forgetfulness infected our post-natal consciousness as well, so that the crumbs (or sparks) of ritual, culture, and heritage that led back to their luminous source in the Book seem scattered beyond recovery? Leaving us in a Diaspora of the spirit, where the rabbis—once so adept at kfitzat ha-derekh, the enchanted seven-league Leaping of the Way—have lost their ability to bounce and delve.

The ancients had a system of interpreting Scripture for which they employed the acronym PaRDeS, literally Hebrew for garden or the Garden. In this way they progressed in their exegeses through four stages, from peshat to reshev, drash, and sod, which corresponded to literal, metaphorical, allegorical, and mystical readings of the text. Thus did their program involve a virtual ascent from the mundane to the sublime.

Virtual for some, because it’s not for nothing that the rabbis voiced their caveat to students beginning their investigations into Kabbalah, that they should have attained at least forty years, have a wife and a bit of a paunch to serve as added ballast in their astral excursions. To wit, the cautionary tale of “The Four Who Entered Paradise,” four rabbis led by the great Talmudic sage Akiva, who mount an expedition to the celestial Eden. Upon entering, one drops dead, another goes mad, and another loses his faith, leaving only Akiva—suffering from PTSD—to come back to the world in one piece. Which is to say that a return to the sources is a journey beyond mere nostalgia, fraught with hazard, and finding your way there is no guarantee you’ll find your way back. Try and follow the example of Akiva and his cronies and, lacking their credentials, you’re likely to lose what little credibility you have and catch hell from critics anxious to remind you that “You’re no Sholem Aleichem, no Philip Roth—tahkeh, you’re no Akiva!”

2015 by the Center for Southern Folklore (from the Peiser Family Collection).jpg) But who am I kidding? Nobody dies or goes meshuggah like Rabbi Akiva’s interloping companions from exposure to a little antique lore; nobody has the sensory equipment anymore even to recognize the power those mothballed narratives once contained. If Akiva were alive today, he’d be sitting in his lonely ostracism from the past like the wounded Fisher King that haunts Eliot’s “Wasteland.” I can picture him, having closed up shop and gone fishing on a planet no longer irrigated by miracles, casting his line into any available stream regardless of its contamination: the Gowanus, say, or Love Canal. And if he should feel a tug at the end of his line—and if the canal pours over a spillway into a channel (call it history) that flows in turn into the sea (call it myth)—if that mossbacked old party feels a tug, he’s likely to ignore it, having no expectation of catching anything anyway, no memory of even what he’s fishing for. But if the tug persists, the rabbi might perhaps wake up enough to call upon a strength he hadn’t known he possessed—a strength belonging to one of his ancestors’ ancestors that compels him to battle his catch with the fervor of Hemingway’s old man.

But who am I kidding? Nobody dies or goes meshuggah like Rabbi Akiva’s interloping companions from exposure to a little antique lore; nobody has the sensory equipment anymore even to recognize the power those mothballed narratives once contained. If Akiva were alive today, he’d be sitting in his lonely ostracism from the past like the wounded Fisher King that haunts Eliot’s “Wasteland.” I can picture him, having closed up shop and gone fishing on a planet no longer irrigated by miracles, casting his line into any available stream regardless of its contamination: the Gowanus, say, or Love Canal. And if he should feel a tug at the end of his line—and if the canal pours over a spillway into a channel (call it history) that flows in turn into the sea (call it myth)—if that mossbacked old party feels a tug, he’s likely to ignore it, having no expectation of catching anything anyway, no memory of even what he’s fishing for. But if the tug persists, the rabbi might perhaps wake up enough to call upon a strength he hadn’t known he possessed—a strength belonging to one of his ancestors’ ancestors that compels him to battle his catch with the fervor of Hemingway’s old man.

It takes him maybe another generation or two to reel it in, aided as he is by his handful of young disciples—callow rabbis and scribes that hang on to him to keep him from pitching headlong into the polluted drink. I don’t expect to live to see it—the Leviathan that is, awesome and shuddering, oily water pouring from its massive silver flanks. But as the rabbi wrestles it triumphantly from the surface of the canal, the monster opens its jaws to show needle-sharp teeth before sliding back into the swill. In its place is another fish, smaller but still monumental, which also opens its mouth to slide back into the toxic soup, leaving a lesser giant still on the line. The rabbi heaves it aloft like a standard to reveal its cankered underbelly and tiger stripes, when it too slips back into its element, leaving Jonah himself hanging from the hook, jabbering a cockamamie yarn about his exploits in the belly of a whale.

Our contemporary authors continue to hold their mirrors up to nature, polished new mirrors that give back with astonishing clarity the stark reality T.S. Eliot said we couldn’t stand too much of. Some hold vintage looking glasses, their mottled surfaces producing funhouse effects whose distortions are often truer than the straight-ahead view. But when I’m widest awake, I still long for the old wonder-struck rabbis with their free-range imaginations, dreamers for whom the mirror was a fluid portal they could pass through with impunity like Alice, returning from the other side with radiant inventions that restore the magic and deepen the mystery.

I believe that a story, if it’s truly kosher, should function as a kind of cosmic template, its narrative tracing a prototypical pattern the way a rubbing traces the relief on an ancient tomb. Then thanks to the conjuring power of language, the story stirs the inanimate; the tomb sculpture rises up and walks abroad like a golem aspiring to humanity. Of course in the bracing old legends golems have the strength to overwhelm us and elude our control. A book may echo the Book more sonorously than the primary noise, a rude awakening but an awakening nonetheless. In the hands of a gifted storyteller a narrative is a map leading back to the story’s own source, and as in the process of tikkun the words return the sparks like a guilty Prometheus to their original flame.

The flame illuminates those places in our consciousness that have since gone dim, but unlike the burning bush this flame can consume; revelation implies the peril of immolation. (Kafka: “A book should be an axe to break the frozen sea within.” Or a flame to melt it.) This is the flame in the jewel of the tzohar that gave Adam, whose formless clay was the original golem, his brief vision of eternity, the light that allows us, here at this darker end of creation, to view the earth in all its manifest beauty and terror from the vantage of Paradise. Then we quickly close the book, extinguishing the flame, though we remain vexed and disturbed ever after by the memory of its stupefying brightness.

So I’m sitting outside the Palace—don’t ask how long! I can’t recall a time when my scrawny nates weren’t numbed by this cold stone bench. It’s been years since I ran out of bribes for the doorkeeper, him with his fancy frogs and epaulettes, his strawberry nose and curling beard, who has frankly grown a bit wintry himself. He took all my gifts with a stiff formality that gave nothing away in return, unless you call his idle remarks about the weather a fair exchange, and the fact that he still tolerates my presence. What haven’t I forfeited to waiting? Beyond my meager wealth, there’s my hair, my failing eyesight, the bodily functions whose loss I’m too weary to be ashamed of, the recollection of who I am and where I came from and what I’m waiting for.

2015 by the Center for Southern Folklore (from the Peiser Family Collection).jpg) So you might say the waiting has become my vocation; though in truth I’m heartily sick of it, if far too confirmed in the habit to give it up. In any case, I sit here beside an overflowing cuspidor, around the corner from the public lavatory—revolting now, though once it boasted an attendant and polished brass pipes—which I must visit ever more frequently. I look vacantly into the street whose rowdy bazaar has long since decamped, leaving behind only weed-ruptured pavement and three-legged dogs. Then up walks this kid, bold as you please. When I’m able to focus, I see this is not the regular delivery “boy,” who’s also grown old, his once-fine kosher meats having degenerated into rag bologna on white bread. This one is sporting an outlandish getup—long caftan, skullcap, corkscrewing earlocks, impish grin; and without ceremony, with maybe a careless yip, he scrambles between the legs of the doorkeeper, who roars in outrage as he turns to chase him into the Palace.

So you might say the waiting has become my vocation; though in truth I’m heartily sick of it, if far too confirmed in the habit to give it up. In any case, I sit here beside an overflowing cuspidor, around the corner from the public lavatory—revolting now, though once it boasted an attendant and polished brass pipes—which I must visit ever more frequently. I look vacantly into the street whose rowdy bazaar has long since decamped, leaving behind only weed-ruptured pavement and three-legged dogs. Then up walks this kid, bold as you please. When I’m able to focus, I see this is not the regular delivery “boy,” who’s also grown old, his once-fine kosher meats having degenerated into rag bologna on white bread. This one is sporting an outlandish getup—long caftan, skullcap, corkscrewing earlocks, impish grin; and without ceremony, with maybe a careless yip, he scrambles between the legs of the doorkeeper, who roars in outrage as he turns to chase him into the Palace.

The next thing I know, from a narrow casement above me, the scrolls of the Law (festooned in costume jewelry) have dropped into my lap, after which the kid himself leaps out and hits the ground running. That’s when I recognize him from a story I didn’t know I knew. This is Hershel Ostropolier, the Jewish Eulenspiegel, a hybrid of Puck and schmuck, hero of a whole cycle of trickster tales; and having escaped some story for the purpose of performing this theft—which seems pointless since he’s clearly not interested in retaining the goods—he’s perhaps on his way to another. Above me the doorkeeper is stuck half-in and half-out of the window, bellowing bloody murder, while Hershel shouts over his shoulder as he runs away: “Life is like a glass of tea!” “Nu?” say I, noticing that my brittle bones have begun to stir; I’m in motion for the first time in memory, following Hershel. “Why is life like a glass of tea?” I shout, and he answers without breaking stride, “Shmendrick, what am I, a philosopher?” So that’s my name, Shmendrick, I think, as hugging the scrolls to my chest I continue to give chase. When last seen we’re still running.

Copyright (c) 2015 by Steve Stern. All rights reserved. Steve Stern, winner of the National Jewish Book Award, is the author of The Pinch, a novel which will be published by Graywolf Press on June 2, as well as several previous novels and story collections, including The Book of Mischief and The Frozen Rabbi. A Memphis native, he now teaches at Skidmore College in upstate New York.

All images copyright (c) 2015 by the Center for Southern Folklore. All rights reserved. The Center for Southern Folklore, located on Main Street in downtown Memphis, is a private nonprofit organization dedicated to documenting and celebrating the people, music, and traditions of the South.