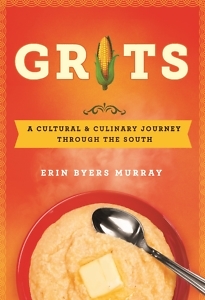

More Than Merely Fuel in a Box

In a new book, Erin Byers Murray tells the true story of grits

Almost every weekday morning, my daughter eats grits. She loves grits, loves them served on a plate, scooped up with a long wooden spoon. She learned to love grits from her father, who likes to simmer his grits with pork stock for added flavor. I like grits, too—I prefer mine fortified by cream and cheese—but I never knew much about the history of this dish until I got the definitive scoop from Erin Byers Murray’s Grits: A Cultural & Culinary Journey Through the South.

Grits have been part of the story of the South as long as the South has been a nameable region—and they were around long before that, too. As with many staples of Southern cooking, it can be difficult to pin their origin to any one cultural group or culinary tradition. The very thing that makes them Southern may be the degree to which they’ve been shared, or stolen. “Name any dish that is considered Southern, trace it back far enough, and you will unearth stories of theft, slavery, appropriation, and loss—as well as evolution, culture melding, and hope,” Murray writes. “The story of grits, today a symbol of both comfort and sustenance, is loaded with strife.”

That story is one of a ground-corn porridge passing from indigenous tribes to European settlers, from slave gardens and kitchens into plantation dining rooms, from small farms to giant corporations. “Like so many Southern foods,” Murray writes, “as grits traveled and transformed, they carried the region’s stories with them.”

And that story includes the unfortunate clutches of Big Agriculture. When corn became a commodity crop in the twentieth century, grits suffered. They became merely “fuel in a box,” cheap and sustaining for hungry people on tight budgets. But if many of us got turned off by grits produced the industrial way, we can’t be blamed: mass-produced corn lost much of its flavor in favor of higher yields and pest-resistance.

The good news is that small-scale growers and millers have kept history alive by cultivating and milling corn in a flavor-forward way. Glenn Roberts, founder of Anson Mills in South Carolina, is arguably the best known “savior of flavor”—he’s the one who turned celebrity chef Sean Brock onto the “terroir in grits,” according to Murray. “Anson’s grains,” she writes, “have become a vessel through which we can explore the history of the South.”

Murray takes readers inside Roberts’s milling operation, and she introduces us to many others who have helped keep history alive over the decades by saving seeds and growing heirloom varieties of corn, or by preparing plates of grits in both traditional and innovative ways, or by writing about grits for readers all over the world. Among others, we meet Betsy and Greg Johnsman of Geechie Boy Mill on Edisto Island, South Carolina; Craig Claiborne, a Southerner who brought the story of grits to the pages of The New York Times; John Coykendall of Tennessee’s Blackberry Farm; and Alabama’s Frank McEwen, whose fate as a miller was sealed when his grits ended up on the menu of Highlands Bar & Grill, the acclaimed restaurant of chef Frank Stitt in Birmingham.

Murray takes readers inside Roberts’s milling operation, and she introduces us to many others who have helped keep history alive over the decades by saving seeds and growing heirloom varieties of corn, or by preparing plates of grits in both traditional and innovative ways, or by writing about grits for readers all over the world. Among others, we meet Betsy and Greg Johnsman of Geechie Boy Mill on Edisto Island, South Carolina; Craig Claiborne, a Southerner who brought the story of grits to the pages of The New York Times; John Coykendall of Tennessee’s Blackberry Farm; and Alabama’s Frank McEwen, whose fate as a miller was sealed when his grits ended up on the menu of Highlands Bar & Grill, the acclaimed restaurant of chef Frank Stitt in Birmingham.

And of course, no deep dive into the grits pot would be complete without a mention of Jimmy Carter, who campaigned with the slogan “Grits & Fritz in ’76,” and who brought the dish to the White House—both as meal staple and as a pet dog named Grits.

While the most celebrated grits lovers have been mostly white men, Murray is careful to note that countless women and people of color have done the hard work of keeping heirloom varieties of corn alive and grits on the table. Women, she reminds us, are the unsung grits-slingers in this foodways narrative, and she sings of several, including Virginia food writer Edna Lewis; the “Original Grits Girl,” Georgeanne Ross; and Julia Tatum, proprietor of Delta Grind in Oxford, Mississippi.

This book is a sensory feast, bound to leave you with a strong craving for grits. Perhaps you’ll be inspired to try one of the recipes that punctuate the text—such as one for shrimp and grits that’s as close as you’re likely to get to the grits-history-making dish created by Bill Neal for Crook’s Corner. My husband served that one up for dinner recently, and it did not disappoint.

As I write this, a bag of stone-ground grits in the cupboard calls to me still, inspiring me to combine one cup grits and four cups water—to add some heat and stir and stir and stir, then top the steaming bowl with a golden pat of butter, seeking the delight and sustenance that simple milled corn can bring.

Susannah Felts is a writer, editor, and educator in Nashville, as well as co-founder of The Porch Writers’ Collective, a nonprofit literary center. She is the author of This Will Go Down On Your Permanent Record, a novel, and numerous journal and magazine articles.