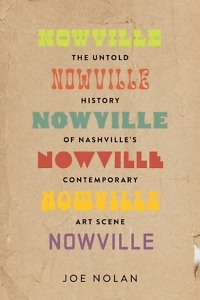

Do-It-Yourself Spirit

Joe Nolan’s Nowville chronicles Nashville’s contemporary art renaissance

Intermedia artist Joe Nolan has covered a wide range of art and film for the Nashville Scene. In his new book Nowville, he tells the story of Nashville’s contemporary art renaissance with a lively oral history featuring numerous artists, gallerists, and curators. Each chapter feels like you’re leaning against a barroom or coffeeshop wall listening to old friends share their love of art.

Nolan, a veteran of the city’s 1990s art scene, displays the depth of his knowledge, sharing origin stories of pivotal organizations like the Untitled Artists group and The Fugitive Art Center. He takes readers into their world of abandoned factories and mills where they endured dust-filled rooms, collapsing floors, and sweltering heat to make art in a creative community. Nowville reveals an infectious do-it-yourself spirit and willingness to take risks at the heart of the movement.

Nolan answered questions from Chapter 16 by email.

Chapter 16: I appreciated your description of Nowville as “a poetic collage of conversations, snipped apart and pasted back together again, into a whole that’s greater than the sum of its parts.” When you began this project, how did you discern that a compilation of interviews was the best approach? And how difficult was it to conduct 80 interviews with 76 people?

Joe Nolan: One reason I didn’t want to write about institutions and commercial galleries is because those stories are readily available at website “About” pages, Wikipedia entries — lots of articles and reviews you can easily find online. But Nashville’s independent, underground, DIY artists, spaces and organizations are harder to track, and an untold story is obviously more appealing to a writer. When I realized I was going to have to rely on interviews, it occurred to me that delivering these voices directly to the reader via oral history was the most potent form. Rewriting all these stories in my own words seemed boring in comparison, and I was keen not to write a boring local history book. Scheduling and recording the interviews on Zoom was pretty easy. Most of them were done in 2022. The pandemic was still winding down, and people were available and wanted to talk.

Chapter 16: Is the renegade spirit of the 1990s still alive in Nashville’s current contemporary art scene? If so, what does it look like in 2024? How is it different?

Nolan: In the first chapter of the book I write about how the key figures of Nashville’s modern art legacy — Aaron Douglas, William Edmondson, and Georgia O’Keefe — brought values of vision, devotion, and generosity to the city’s visual art scene. Those values are still in play today. Untitled was as much a concept as it was a group, and their uncensored, uncurated pop-up displays brought do-it-yourself, punk rock values to the table. Those are still here, too, but the context is totally different. Nowadays there are lots of legitimate opportunities for emerging and unschooled artists to show in galleries and other art-focused spaces. But the artists have a much harder time finding affordable spaces to work or curate in. We’re seeing the rise of independent, itinerant curators who are guest programming in commercial galleries and popping up in collaboration with other art-centric or art adjacent spaces. We’re also seeing a return to domestic studios and gallery spaces — they’ve been a Nashville thing since William Edmondson turned his front lawn into an art gallery for his sculptures back in the 1930s.

Chapter 16: I’m embarrassed to admit I didn’t know about William Edmondson before reading Nowville. Edmondson, a native Nashvillian and sculptor, was the first Black artist to have a solo exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art, in 1937. In the first chapter, you write about the importance of his legacy in Nashville’s modern art history. When did you learn about Edmonson’s legacy? And how can Nashville better honor his artwork and accomplishments?

Nolan: I got very close to Edmondson’s story and his work in 2000 when I was part of the crew that was hired to install The Art of William Edmondson exhibition at Cheekwood Museum in Nashville. Cheekwood curator Rusty Freeman was a great guy with lots of enthusiasm for Edmondson and his work, and he taught all of us everything you might want to know about the sculptor. I built countless platforms and pedestals for that show. We even built a recreation of the façade of Edmondson’s outdoor workshop as part of the title wall. That show travelled from Nashville to four other institutions, including the Museum of American Folk Art in New York City. It put Edmondson back in the national art conversation, and today he’s regarded as the great folk carver of the 20th century. There’s an art park named for him in North Nashville — you can see Thornton Dial and Lonney Hollie sculptures there. Edmondson’s homesite is also a park with a Tennessee historical marker.

Nolan: I got very close to Edmondson’s story and his work in 2000 when I was part of the crew that was hired to install The Art of William Edmondson exhibition at Cheekwood Museum in Nashville. Cheekwood curator Rusty Freeman was a great guy with lots of enthusiasm for Edmondson and his work, and he taught all of us everything you might want to know about the sculptor. I built countless platforms and pedestals for that show. We even built a recreation of the façade of Edmondson’s outdoor workshop as part of the title wall. That show travelled from Nashville to four other institutions, including the Museum of American Folk Art in New York City. It put Edmondson back in the national art conversation, and today he’s regarded as the great folk carver of the 20th century. There’s an art park named for him in North Nashville — you can see Thornton Dial and Lonney Hollie sculptures there. Edmondson’s homesite is also a park with a Tennessee historical marker.

Chapter 16: It occurred to me as I was reading Nowville that it is not only an oral history but a map. The chapters take the reader across the city through neighborhoods, industrial areas, and prominent spots. And I appreciate the “Cast Members” section as a reference for identifying leaders in Nashville’s contemporary art scene. For young artists or newbies, Nowville offers a way into the Nashville art community by learning its history. And for artists seeking a creative community, the book offers a model for those with a DIY mindset. Did you intend for the book to both preserve history and show a way forward? In what ways do you hope Nowville will help young artists, curators, and gallerists?

Nolan: I didn’t want to over-explain the people or locations in the book, and my editors at Vanderbilt University Press and I worked together to clarify what we needed to without weighing down the conversations with timelines and actual maps, etc. We thought about a lot of that stuff at different points, but, ultimately, it’s a book about the stories these people tell. Sometimes they even give contradictory accounts of a place or a situation. I think those are some of the funniest moments in the book.

Filmmaker Werner Herzog said, “Facts do not constitute the truth. There is a deeper stratum.” Nowville is about the deeper truths in personal memories and stories. The book is definitely an archive of these places and people, collected and made accessible for the first time. It’s not really a handbook of DIY art strategies, but there are lots of ideas and examples that I hope young artists in another small art scene might take inspiration from. We talked about adding some kind of conclusion that would tie the book up in a bow, but I never wanted to do that. I love predicting art trends in my columns and reviews, but here I just wanted to celebrate these people and their unlikely accomplishments by letting them speak for themselves.

Chapter 16: You explain in Nowville that the impetus for the 1990s movement grew out of frustration with Nashville’s traditional art institutions. Decades later, has the gap between traditional art institutions and do-it-yourself art movements become narrower or wider? Have barriers been removed between the two or increased?

Nolan: The biggest problem was a lack of places to show work. That was exacerbated by the fact that, at that time, local galleries weren’t looking to nurture the careers of local emerging artists. The art establishment was very small and tangled up with academics, and if you were an artist without an MFA or an established audience, it was pretty much impossible to find gallery representation.

But it’s very different today. Now there are many more commercial galleries and artist-led spaces that regularly feature local emerging artists. Art galleries like Elephant have built a reputation on showing unschooled artists. Part of this is just postmodernism flattening the hierarchy of high and low art and erasing boundaries between art and craft and design. But the other reason is that the DIY projects in Nowville served as a proof of concept, demonstrating that there was real talent, creative organizing, and productive practices happening right here in the city limits. To their credit, Nashville’s galleries and institutions caught up fairly quickly, and nowadays it feels like the whole visual art scene is mostly united against bigger threats like displacement.

Chapter 16: The final chapter in Nowville focuses on North Nashville’s rich history of contemporary art. In recent years, the murals in “Norf” have received significant attention. But I was unfamiliar with Carlton Wilkinson and his gallery. His vision and guidance in shaping the contemporary art scene, along with founding the Nashville African American Arts Association, is impressive. Who is another artist, curator, or gallerist from Norf’s contemporary art scene that deserves attention?

Nolan: I just gave a Best Independent Curator notice to Evan Brown in the Nashville Scene’s 2024 “Best of Nashville” issue. As I mentioned, independent curators are playing bigger roles in the art scene since gallery spaces are harder to come by, and Evan is at the front of that pack. He started at the NKA space in North Nashville and still curates the NKA Gallery in Memphis. He joined my Nowville panel at the Southern Festival of Books and talked about the contemporary art scene in Nashville. He has lots of insights into what’s become the Buchanan Arts District because he was one of the people who helped build it.

Billy Kilgore is a writer, at-home dad, and ordained pastor. He lives with his wife and two sons in Nashville. His writing has appeared in The Washington Post’s “On Parenting” column, Narratively, Scary Mommy, and Fatherly. He is a graduate of the University of Tennessee at Chattanooga.