An American Literary Life

Frye Gaillard discusses Jimmy Carter’s love of the written word

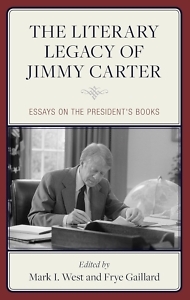

When Jimmy Carter died last December at age 100, the obituaries naturally focused on his presidency, as well as the humanitarian and human rights work that earned him a Nobel Peace Prize. His prodigious literary output didn’t get a lot of attention, but as Mark West and Frye Gaillard point out in their introduction to The Literary Legacy of Jimmy Carter, he penned more than 30 books without the help of a ghostwriter, and his writing “provides a window into the workings of his mind.”

The 22 essays in the anthology, contributed by scholars, journalists, and one poet, survey the breadth of Carter’s body of work, from memoir and fiction to controversial political analysis, and they provide much insight into the genesis of the books and how their author viewed them. The book also includes an extensive bibliography of resources on Carter’s writing.

The 22 essays in the anthology, contributed by scholars, journalists, and one poet, survey the breadth of Carter’s body of work, from memoir and fiction to controversial political analysis, and they provide much insight into the genesis of the books and how their author viewed them. The book also includes an extensive bibliography of resources on Carter’s writing.

Frye Gaillard describes The Literary Legacy of Jimmy Carter as “the brainchild” of his co-editor Mark West, who has written or edited 21 books, including Theodore Roosevelt on Books and Reading. Gaillard himself interviewed Carter multiple times over the years for a series of articles and for Gaillard’s 2007 book, Prophet from Plains. He answered questions about The Literary Legacy of Jimmy Carter by email.

Chapter 16: Charlotte Pence’s essay about Jimmy and Rosalynn Carter’s post-presidency memoir Everything to Gain notes the sharp, almost shocking cultural and political differences between the U.S. of the 1980s and now. Were you struck by that as you worked on this book? Did you ever feel you were exploring work from a distant era?

Frye Gaillard: I thought Charlotte’s essay was one of the strongest in the book. In a way, it does offer a startling contrast between our self-involved culture of today and the moment when Jimmy and Rosalynn Carter were processing the former president’s electoral defeat in 1980. But to me, as with so much about the Carters, their message represents a kind of timeless rebuke to the selfishness and growing indifference to the common good that we see and feel all around us today.

This chapter recounts the Carters’ decision to reclaim meaning in their own lives — even in the face of bitter disappointment — by charting a course of service to others. On the surface, that service may have seemed improbably sacrificial — all those hours, for example, in the hot summer sun building houses for Habitat for Humanity. Or their arduous travel to disease-ravaged developing nations trying to stamp out Guinea worm. But in their various memoirs, invariably written with straightforward accessibility, the Carters present the counterintuitive truth of lives made richer by sacrifice — by a pursuit of meaning and purpose much larger than themselves.

Chapter 16: I was surprised to read in Emily Seelbinder’s article that Carter had to work hard to get his publisher to release Always a Reckoning, his poetry collection, and they paid very little for it. Did he have that same dogged belief in all his writing?

Chapter 16: I was surprised to read in Emily Seelbinder’s article that Carter had to work hard to get his publisher to release Always a Reckoning, his poetry collection, and they paid very little for it. Did he have that same dogged belief in all his writing?

Gaillard: I think he did. Carter was nothing, if not dogged. Stubborn. Tenacious. He loved poetry and when he decided to write it himself, he made a pilgrimage to Arkansas to work with the award-winning poet, Miller Williams, who is known to some of us for two things. He was the father of singer-songwriter Lucinda Williams, and he was the Inaugural Poet at Bill Clinton’s second swearing in. (Maya Angelou was the poet at Clinton’s first.)

Anyway, Williams reported that Carter was an eager and accomplished pupil whose poetry deserves to be taken seriously. People close to Carter have remarked on the level of satisfaction — to some extent unexpected — that Carter found in the written word, no matter the genre in which he was working.

Chapter 16: Carter famously refused to use ghostwriters, and his sole novel, The Hornet’s Nest, got high marks for research and accuracy but was described by one reviewer as “an epic slog.” What’s your frank opinion of his writing gifts and prose style overall?

Gaillard: Having read The Hornet’s Nest, I would agree with that assessment of it. In preparing to write this historical novel, Carter obviously taught himself a lot about the Revolutionary War. But the book in places is, in fact, a bit of a slog.

I also thought Carter’s memoirs about the various stages of his life could be uneven. Cynthia Tucker and I wrote the chapter in this book about Beyond the White House, the former president’s account of his work at the Carter Center. There were moments, to me, when that book read like an annual report.

That said, I also wrote the chapter about Carter’s presidential memoir, Keeping Faith, and I thought it was riveting. Not only did it describe dramatic historical events like the Camp David peace negotiations, it also demonstrated Carter’s quite remarkable sense of story. Keeping Faith begins and ends with his last day in office when he was working — doggedly and successfully — to achieve the release of U.S. hostages held in Iran.

In addition to this presidential memoir, my co-editor Mark West and I agree that Carter’s best, most deeply felt book was probably An Hour Before Daylight, his reflections on his Depression-era boyhood outside of Plains. It is both tender and candid, quite revealing, among other things, about his youthful encounters with Jim Crow.

Chapter 16: There’s a quote in one of the essays from Carter biographer Douglas Brinkley, noting that Carter was sometimes accused of dropping names like James Agee and Dylan Thomas as a “political ploy” to attract young people and intellectuals. Do you think there was ever any insincerity in his public passion for literature? Was there a touch of the dilettante about him?

Gaillard: I’m not a big fan of Douglas Brinkley, and I’m not sure I agree with him about that. I mean, maybe some people thought Carter’s references to Dylan Thomas — or Bob Dylan, for that matter — were a “ploy.” But I don’t think so. I think he was genuinely moved by the written word.

Chapter 16: Surveying Carter’s literary output necessarily creates an overview of his life and presidency. A common assessment is that his years out of office were more successful than his time in the White House. What do you think?

Gaillard: I think there is both truth and oversimplification in that statement. I think Carter’s life after the White House certainly became the gold standard for a vigorous post-presidency — in ways that were sometimes surprising. He did not, for example, always assume the stance of an elder statesman above the fray. His most controversial book, Palestine: Peace Not Apartheid, angered many Israelis and Jewish Americans. And Nancy Mitchell’s chapter about that book is one of the strongest essays in The Literary Legacy of Jimmy Carter.

But I agree with Carter biographer Jonathan Alter that Carter’s time in the White House represented a consequential presidency. The Camp David peace accords between Israel and Egypt were certainly a monumental achievement. In her chapter in our book, Charlotte Pence writes about President Carter presiding over a dramatic increase in the rate of childhood vaccinations. And in managing the moment that probably cost him reelection — the Iranian hostage crisis — Carter’s diplomacy not only kept our diplomats alive, but brought them all home. The glib inclination to give President Reagan credit for that was simply not true.

That said, Reagan did possess a presidential quality that Carter lacked — the ability to communicate, to convince the American people that both he and the country were on the right track. To me, that is the great irony in the life and career of Jimmy Carter. Fundamentally, the lack of that particular skill — of communicating in the moment a compelling political vision for the country — was the reason he was a one-term president.

But as The Literary Legacy of Jimmy Carter seeks to make clear, his was a singular American life — a journey shared with a wife of more than 70 years, trying to make the world a better place. To a remarkable degree they succeeded. And without question, Jimmy Carter’s decency offers a strong and durable affront to the corrosive cynicism of our time.

Maria Browning is a fifth-generation Tennessean who grew up in Erin and Nashville. Her work has appeared in Guernica, Los Angeles Review of Books, Literary Hub, and The New York Times. She’s the editor of Chapter 16.