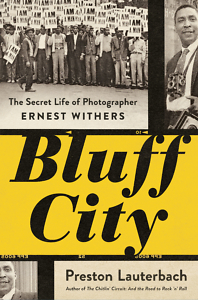

A Flawed Hero in Tumultuous Times

Preston Lauterbach’s Bluff City looks at the strange legacy of a civil-rights figure who worked as an FBI spy

Memphis is a place of “dangerous politeness and sticky charisma,” Preston Lauterbach writes in Bluff City, a title that describes both the city’s site above the Mississippi River and the posturing of its inhabitants. Bluff City’s subject is Ernest Withers, the polite and charismatic Memphis photographer who covered crucial moments of the civil-rights era while also acting as a spy for the FBI.

Photographs by Withers are burned into the national memory. Emmitt Till’s great-uncle standing in a Mississippi courtroom in 1955 to point to one of the white men who murdered the fourteen-year-old boy. Martin Luther King Jr. on a Montgomery bus the day court-ordered desegregation of the city’s public transportation went into effect. Dozens of Memphis garbage workers holding up the “I Am A Man” signs they would carry in a 1968 march led by King, a week before he was assassinated in Memphis.

When stories by the virtuoso investigative reporter Marc Perrusquia about Withers’s secret job as a paid government informer were first published in The Commercial Appeal in 2010, three years after the photographer’s death, they stunned Withers’s admirers, his friends—some of them the subjects of photos he sold to J. Edgar Hoover’s FBI—and even his adult children. Perrusquia described how he got that story, and how Withers’ identities as journalist and informant merged, in A Spy in Canaan, published in 2018.

In Bluff City, Lauterbach—who has also written an excellent history of Memphis’s early days, Beale Street Dynasty—focuses on a remark Withers made during an interview recorded in 1982. It was a seeming admission that he had, though “not by plan,” helped set the scene for the violence that derailed King’s 1968 Memphis march. Withers and two friends bought the lumber and sawed the sticks attached to the “I Am A Man” signs which sanitation workers carried in that march. Those sticks were later used to break storefront glass, which helped set off the chaos that turned the march into a battle between police and protesters.

In attaching sticks to those signs, was Withers laying the groundwork for his “I Am A Man” photograph, which became an essential symbol of the garbage workers’ simple longing for economic justice? Or could he have been compromising the march itself on behalf of the FBI? It’s a question Lauterbach asks but can’t answer.

Withers’s Beale Street studio was an easy stop for many of the key players in the local movement. He was accessible to Nation of Islam organizers and to the black activists known as the Invaders. He was in regular contact with Jim Lawson, who had invited King to Memphis. Because of his often brave work as a journalist, he was trusted as an insider. Lauterbach sets Withers and his camera down in some of the most important moments in U.S. history: the Till trial, the integration of Central High in Little Rock and the University of Mississippi, the funeral of Medgar Evers—where Withers was beaten and arrested—the final march, and the assassination of King. But he also had a large family to support and expressed some bitterness about how little he was paid for covering some of those great moments of history.

Withers’s Beale Street studio was an easy stop for many of the key players in the local movement. He was accessible to Nation of Islam organizers and to the black activists known as the Invaders. He was in regular contact with Jim Lawson, who had invited King to Memphis. Because of his often brave work as a journalist, he was trusted as an insider. Lauterbach sets Withers and his camera down in some of the most important moments in U.S. history: the Till trial, the integration of Central High in Little Rock and the University of Mississippi, the funeral of Medgar Evers—where Withers was beaten and arrested—the final march, and the assassination of King. But he also had a large family to support and expressed some bitterness about how little he was paid for covering some of those great moments of history.

Like others who have confronted the Withers legacy, including those whose own activities were documented in FBI files stocked with Withers’s photos and reports, Lauterbach struggles to understand his subject’s inner conflicts and loyalties. An Army veteran, Withers was a conservative patriot who disapproved when the civil-rights movement took an anti-Vietnam War turn. Hints of communism among civil-rights activists disconcerted him and obsessed the FBI.

Lauterbach doesn’t elaborate on the closing chapter in Withers’s work for the government, when the photographer himself became the subject of an FBI sting operation for selling prison pardons while working in a corrupt state administration. He consigns the interlude to an afterword: “[Y]ou can see some positive in Withers’s pay-for-parole involvement. He helped free a young African American man who faced a lengthy prison term for a first offense.”

In short, Ernest Withers was a fascinating man. Even if he had lived to address questions about the contradictions in his personal history, clarity might not have been the result. As Lauterbach learned in his own reporting: “Memphis people didn’t answer straight.”

Peggy Burch was books editor at The Commercial Appeal in Memphis for ten years, and she also worked as a deputy metro editor and Arts & Entertainment editor for the newspaper. She is a graduate of the Newhouse School of Public Communications at Syracuse University and holds a master’s degree in English literature from the University of Mississippi.