A Timely Reckoning

The Cherokees fills an important niche in our understanding of a vast and contradictory history

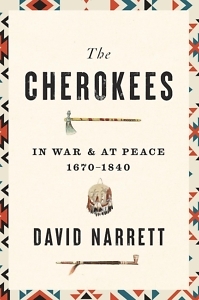

“Tennessee” is derived from the Cherokee noun Ta-Nas-Ce, “river with a big bend,” which could allude to scores of streams and meanders in the state’s watershed but likely refers to a bend and village along the Little Tennessee River in the foothills of the Smoky Mountains. David Narrett’s magisterial, detailed The Cherokees: In War and at Peace, 1670-1840 maps the Indigenous nation’s outsized influence on the history of the republic that dispossessed them of so much land and esteem.

Narrett, a professor at the University of Texas at Arlington, flexes his academic muscles here, tracing the trajectory of the Cherokees from their initial brushes with Europeans to the Trail of Tears, just prior to the Civil War, when East Tennessee served as a point of embarkation. He offers crucial background: Cherokee speech, for example, belongs to the Iroquoian language family, unique among Native tongues in the South, suggesting an earlier migration from the Great Lakes region and a sense of remove from neighbors. They often skirmished with other Indigenous groups. They observed a color protocol: red dress and banners signaled conflict while white indicated coexistence and fruitful dialogue. When colonists encountered the Cherokees in the late 17th century, the Natives were clustered amid mountains and tributaries in present-day Georgia and the Carolinas — small settlements known as the Lower and Middle Towns — and those on the western flanks of the Appalachian divide (Overhill Towns). Political authority was diffuse, drawing, at the local level, on egalitarian ideals such as income redistribution.

The Cherokees devotes a sizeable chunk of chapters to the 18th century, as the villages found themselves pawns in the bloody struggles between the British and French empires. Their formidable rivals, the Creeks, also challenged their territory, sparking a frenzy of alliances, sudden betrayals, and treaties rarely honored. “Though the Shawnees and Cherokees were former adversaries, their old enmity was not a barrier to cooperation when both parties had something to gain,” Narrett writes. “Creative Native diplomacy came to the fore as a counterweight to chaos, displacement, and violence.”

He’s particularly strong in depicting the essential role women played in brokering peace. “Cherokee women maneuvered on a diplomatic front outside formal Native-colonial conferences. It was precisely when official negotiations were in disarray that women’s influence was most keenly exerted.”

The Cherokees even dispatched a delegation of leaders to London, where they were treated with genuine awe, feigned deference, and racial condescension. There’s quite a bit on the machinations of the Yamasee War and later campaigns. Narrett’s book is scrupulously dense — sometimes dry — but it’s an invaluable contribution to this fractious history. The author weaves in cultural anecdotes, limning the sophisticated art and practices in Cherokee ceremonies: “This was no European masked ball. Cherokee masks embedded supernatural forces. Carved from wood and often adorned with animal fur and paint, masks had phantasmagoric qualities, displaying a man’s nose as phallus or taking the form of a wasp nest, an animal’s features, or a human head crowned by a coiled rattlesnake.”

The Cherokees even dispatched a delegation of leaders to London, where they were treated with genuine awe, feigned deference, and racial condescension. There’s quite a bit on the machinations of the Yamasee War and later campaigns. Narrett’s book is scrupulously dense — sometimes dry — but it’s an invaluable contribution to this fractious history. The author weaves in cultural anecdotes, limning the sophisticated art and practices in Cherokee ceremonies: “This was no European masked ball. Cherokee masks embedded supernatural forces. Carved from wood and often adorned with animal fur and paint, masks had phantasmagoric qualities, displaying a man’s nose as phallus or taking the form of a wasp nest, an animal’s features, or a human head crowned by a coiled rattlesnake.”

As Kathleen DuVal notes in her recent Native Nations, greater tragedy befell Indigenous peoples after the American Revolution. Narrett probes how a rapidly expanding U.S. seized lands and pushed the Cherokees further west, fanning across the Chickamauga towns. Imperiled, these disparate communities banded together, guided by an array of impressive public figures, including Nan-ye-hi, better known by her English name, Nancy Ward, a negotiator with the British, unprecedented among Cherokee women; Chief John Ross, only one-eighth Native, who bargained futilely with Andrew Jackson; and Sequoyah, whose syllabary of the language was its own genius. I felt a shiver of sorrow as I read about these exemplars, who fought off displacement and despair for as long as possible, whose every act of good faith was cut down by Manifest Destiny.

Make no mistake: The Cherokees is foremost a commanding work of scholarship, akin to New Blackhawk’s National Book Award-winning The Rediscovery of America, its themes illuminating the fetid corners of the American Experiment. Narrett achieves the goal he set (and then some), filling an important niche in our understanding of a vast and contradictory history. We can either learn from the past or repeat its folly. The choice faces us not next decade or next year — the moment of reckoning is now.

Hamilton Cain is the author of This Boy’s Faith: Notes from a Southern Baptist Upbringing and a frequent reviewer for a range of publications, including The New York Times Book Review, The Washington Post, and The Boston Globe. A native of Chattanooga, he lives in Brooklyn, New York.