An Unbroken Thread

Poet Jesse Graves discusses his fourth collection, Merciful Days

These days especially, we crave mercy, that plenitude both given and received in times of loss and uncertainty. Such benevolence and kindness infuse East Tennessee poet Jesse Graves’ fourth collection, Merciful Days, an expression his mother used often. Despite his many losses — father, brother, a favorite uncle — Graves is rarely alone in his native valleys and ridges of Sharps Chapel in Union County, ancestral land rich with the spirits and stories of great-greats and beyond, each “a broad old footprint.”

In haunting lyric poems and traditional narratives, Graves shows us these ‘ghost-lives’ that shaped the boy learning the rough language of cows and that imprint the returning adult who walks the fence line now without his father. He slows our busyness and distraction, draws us into time’s shimmer in this particular place, his childhood’s almost mythical forest and cove where “the world held us like a cup,” where history and even prehistory move like a “nameless river.”

In haunting lyric poems and traditional narratives, Graves shows us these ‘ghost-lives’ that shaped the boy learning the rough language of cows and that imprint the returning adult who walks the fence line now without his father. He slows our busyness and distraction, draws us into time’s shimmer in this particular place, his childhood’s almost mythical forest and cove where “the world held us like a cup,” where history and even prehistory move like a “nameless river.”

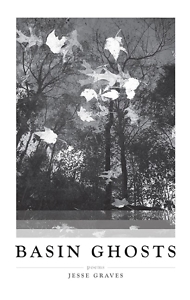

It is fitting that this book was released in October, when the veil is traditionally believed thinnest between the present and the otherworld, for Graves seems as familiar with the other side as with the sage grass at his feet. And fitting to clasp the locket of these elegies close, like a reunion photograph with his beloved dead appearing like “eternals,” yet fleeting and taking those merciful days with them. In fact, the striking cover with its murmuration of swallows vibrates in motion, those shades of remembrance weaving above us, “a sound like wind/coming to life.” Yes, now more than ever, bring us mercy. Bring us the enduring, healing power of home to reconcile the lost with the found in our lives.

Note: I’ve known Jesse Graves for many years, since he was an undergraduate at the University of Tennessee, Knoxville. I’ve admired his poetry and critical work as it deepened over time and am proud of his work now as poet-in-residence and professor of literature and creative writing at East Tennessee State University. He answered questions for Chapter 16 via email.

Chapter 16: You navigate many losses in Merciful Days while keeping a careful balance between emotion and restraint. Are you conscious of maintaining that balance and avoiding sentimentality in your work, especially in memory poems?

Jesse Graves: Thank you for recognizing the balance that I am continually hoping to maintain. I realize the danger of sentimentality with my subject matter, and even with my way of seeing and processing the world. A lot of people and places I care about are gone and are not coming back. I always remember something the great Jack Gilbert said in response to a poem of mine in workshop: “Sentimentality is the risk most worth taking in poetry.” He said that poets should be willing to go where their real feelings take them, because that is where the most important discoveries can be made in poetry. I have realized through the years that most of the poems I really love, and truly care about, from passages of The Odyssey to Joy Harjo’s “Remember,” take that risk.

Chapter 16: Writing in times of loss can move our emotions outside of ourselves as we shape a poem or story — and often helps us travel through grief to a place of acceptance. Did writing these poems help in your grieving process?

Graves: Writing and revising these poems did help me manage my grief over the loss of close family members, though it sometimes takes a while for me to see how the poems will come together. One of the poems from early in the book, “Nameless River,” seems now like a fairly straightforward memory poem about trying to recover a name from my dad’s past, but it was the hardest poem in the whole book for me to figure out.

Trying to articulate all that was lost to me when my dad passed felt too daunting to even ponder, but I desperately needed to recall that name, the man who gave my dad his first independent opportunity. I realized that for every puzzle I solved, countless others would remain in fragments, but I felt a deep connection to my dad when I unearthed the name of Clyde Ivey, who died many years before I was born but was important to me, nevertheless.

I have thought of Merciful Days as the book of my mother’s voice, and the title phrase comes from an expression of her grief, which is an essential part of what we have shared and a weight we have tried to carry together.

Chapter 16: In setting much of your poetry in your native Tennessee community of Sharps Chapel, you’ve created a microcosm that contains the universe — much as fellow Tennessean Charles Wright does from the view of his land in Montana. Could you share your thoughts on the relationship between the particular and the universal? How do you navigate that relationship in your writing?

Graves: Thank you for that encouraging comment. Charles Wright has been one of my favorite poets for most of my writing life, and I have learned so much about how poems can be put together from reading his work. I am sure that I was subconsciously imitating Wright for a decade or more, only to finally realize that his genius was not a transferable skill!

I have been reading Catharine Savage Brosman’s New Mexico and New Orleans poems recently, which were a gift from my Louisiana-poet friend John Freeman. I find a beautiful sense of place in many of her individual poems, but I also feel a larger canvas that somehow unites them, that I think must simply be her specific voice and sensibility.

I’ve wondered about this issue through the years and always considered that Seamus Heaney’s poems were the perfect model of getting to a universal understanding through the particular individual experience. I relate to his poems so directly, though I’ve never been to Ireland, much less to Mossbawn, and yet it feels as real to me as my own Sharps Chapel.

Chapter 16: Following that line of thought, how is your work fully of the southern Appalachian region yet transcending the region?

Chapter 16: Following that line of thought, how is your work fully of the southern Appalachian region yet transcending the region?

Graves: I believe I would probably limit the range where my work represents with any authority down to the locations in East Tennessee I have written about, my homeplace in Union County, a few parts of Knoxville, Johnson City, and the Roan Mountain area. I never really came across the idea of Appalachian literature until I was in college, reading Lee Smith’s fiction in Dr. George Hutchinson’s Intro to American Studies course at UT.

I also wrote my first real personal essay in that class, about my ancestors in Sharps Chapel, of course. It was called, “History of a Small World.” I don’t think my family really identified as natives of Appalachia when I was growing up, but just as general country people. I think there is some continuity in those rural experiences — I felt them in college when I read The Woodlanders by Thomas Hardy and O Pioneers by Willa Cather, and more recently in the fiction and essays of the English pastoralist Richard Jefferies. I hope that readers from anywhere and everywhere would find something to relate to in the lives I have written about and in the places I know most personally.

Chapter 16: There are ghost stories and haints galore in Merciful Days. How do hauntings work in your writing, especially as grounded in Appalachian traditions?

Graves: Well, I was raised in a traditional Appalachian “dark holler,” where we could not see or hear our nearest neighbors and the road that passed was named for an early 19th-century woman believed to have been a witch. I love the folklore of the community, but I also had a spooky enough childhood to not be willing to say for sure that none of it is true. I cannot explain all that I have seen.

Ghost stories, though, are not only about the past for me. I have been fascinated for years by this concept of “hauntology,” which originates with Jacques Derrida’s Specters of Marx, and the idea of “lost futures” as described Mark Fisher, who talked about a nostalgia for all the possible futures that have been closed off to us by circumstance. I see it all around when I visit Sharps Chapel. I calculated this recently: Nearly half of the boys from my tiny elementary school who were in my grade, and one grade above and below me, have spent time in prison or have died. It feels eerie to think about a vanished generation and the haunted state of being they have left behind.

Chapter 16: Numerous poems also spring from waking dreams and dreams of sleep, both yours and your mother’s. Writing from dreams can be tricky, whether to shape them as surreal or realistic. How do dreams take you further into the heart of your poems’ mysteries?

Graves: It’s funny you should mention this idea — the manuscript of poems I was writing alongside the Merciful Days poems is tentatively called Across the River of Waking Dreams. I don’t think I have mentioned that to anyone, so I don’t think you could have known. Those kinds of symmetries further convince me that a poet’s world is mostly a dream world. The mind I am in when I write my poems feels somewhere in between the way I feel when I am asleep and dreaming and when I am awake and working on other things like grading papers or buying groceries. In my own experience, poems are like dreams, kind of elusive, and they need a lot of room to run around before I can settle them down into words. A poem can escape just as quickly as a dream fleets away after waking up.

Chapter 16: In the poem “Wind Work,” you indirectly mention the coming of Norris Dam/Norris Lake, which submerged your family’s land. How has this loss reverberated through your family generationally and what metaphors does it bring to your writing?

Graves: The changes brought by the TVA’s Norris projects have been a persistent theme in my writing — the title of my second book of poems, Basin Ghosts, comes from a line in a poem about the TVA removals. Those changes are fundamental and ongoing, too, with most of the new development in Sharps Chapel happening in gated communities on the banks of Norris Lake. It amounts to a kind of rural gentrification that I haven’t seen written about very much.

I think the effects on my family gave me a sense of the impermanence of living in place. The land itself changes, and our relationship to it can change drastically and suddenly even if we do not want it to happen. It also helped me to think about how Sharps Chapel was contested land and about the Native people who lived here before my ancestors arrived. When I was a child, it was thrilling to dig around in the creek beds and find arrowheads, but it gave me a sense, even then, of how much things could change over time.

Chapter 16: You have studied with poets Jack Gilbert, Robert Morgan, and Arthur Smith and interviewed Charles Wright and David Madden. How would you say your work is in conversation with other works of literature, both within and outside the Appalachian region?

Graves: I sometimes cannot believe the good fortune I have had with teachers in my life, and with my opportunities to learn directly from amazing writers. Connie Jordan Green was my first poetry instructor at UT, followed by the true Dream Team of Marilyn Kallet and Arthur Smith, whose styles and approaches were perfectly complementary for a young poet to learn from. I studied with Robert Morgan and Kenneth McClane at Cornell, and to me, Morgan is the quintessential writer of Appalachian experience. I got to know A.R. Ammons, too, who was semi-retired, but came to campus every morning to visit with whoever wandered by the Temple of Zeus coffeeshop in Goldwin Smith Hall. Ammons gave me one of the best pieces of advice I ever got for my poetry, and one of the simplest: He said, “You need more hard sounds in these poems.” At that time, I was a young poet stoked about Hart Crane and John Keats, in love with pure lyricism, and those early poems of mine needed an edge to them.

Every writer has their own lineage of the books they have read, the teachers they have learned from, the readings and conversations and bookstores that have shaped them. I suppose I am writing back to say thank you to Walt Whitman and Emily Dickinson just as much to Robert Morgan, who helped me choose the poems for Merciful Days. Literature feels like an unbroken thread, connecting people through time and across continents, and that has helped me understand the continuities and the particularities of my life. I hope my own writing is an expression of gratitude to those who made the effort to leave a record of what they experienced in their times and places.

Linda Parsons is a poet, playwright, and the copy editor for Chapter 16. She is the poetry editor for Madville Publishing and reviews editor for Pine Mountain Sand & Gravel. Her fifth poetry collection is Candescent (Iris Press, 2019).