Garden Secrets

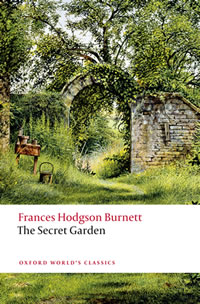

On the sesquicentennial of The Secret Garden, Michael Sims considers the surprising connections between his own Crossville boyhood and Frances Hodgson Burnett’s masterpiece

I was embarrassed to find myself crying. I was more than embarrassed; I was astonished. I seldom even got tears in my eyes and I almost never actually cried. (I wrote these sentences in past tense because I’ve become more sentimental over the years.) It was 1993 and I was thirty-five years old. Sitting in Vanderbilt University’s Sarratt Cinema with a companion, I was watching what I had thought was a rather innocent-minded movie, admiring the cinematography and enjoying the safely distant Edwardian tribulations of three English children. Then, suddenly, I was crying.

The movie was Agnieszka Holland’s adaptation of The Secret Garden, based closely upon Frances Hodgson Burnett’s great novel. I had only recently read the book for the first time and had found its lush hybrid of nature worship and coming-of-age story irresistible. Naturally I had to see the movie. I had never gotten around to Fred M. Wilcox’s 1949 adaptation, so I didn’t know quite what to expect, how the story might translate into film. What I didn’t foresee was that the movie would tap instantly into my own emotional life as a child. I ought to have known. My childhood had featured emotional turmoil and isolation, a suddenly dead parent, a deep spiritual and intellectual response to the natural world around me, and even a stint in a wheelchair—in my case, because of rheumatic fever and the resulting juvenile rheumatic arthritis.

It was the wheelchair scene that got me in the movie, of course. Throughout, I had been identifying more than I realized with the adventures of sad, plain little Mary, who has lost her parents to a cholera outbreak in India and who finds herself reluctantly lodged at a relative’s country estate back home in chilly England. Her only companions are the privileged brat Colin, who turns out not to be crippled and who regains his own lost father’s love, and homespun Dickon, whose human dialect can be nearly indecipherable but who almost speaks the language of his wild-animal pets. In retrospect I find it easy to see that each child spoke to a different aspect of my own childhood experience and yearnings. But I didn’t think of that at the time. When Colin rose from the wheelchair, healed by the other children’s innocent affection and his own determination—in short, cured by the secret walled garden where it was safe to be a child—I lost it. As the tears ran down my face, my companion looked as surprised as I felt.

As soon as a book or movie or painting captures my imagination, I begin to peer into its biographical and contextual history. I now own Gretchen Holbrook Gerzina’s Annotated Secret Garden, which W. W. Norton published in 2007 in their ongoing series of classics, luscious oversize volumes complete with marginal annotations and usually containing the original illustrations. I have a Norton Critical Edition of the book, also edited by Gerzina, and her biography of Burnett, along with other editions.

These sources fed my curiosity about Frances Hodgson Burnett—and I found some parallels between her life and my own. Like me, she lost her father at the age of three. Far more surprising was my discovery that we shared a landscape: I was a child in Cumberland County, Tennessee, in the 1960s; a century earlier this quintessentially English author had herself been a child in nearby Knoxville. I remember exclaiming aloud, when I read this biographical tidbit, “What? Knoxville?” In 1863, the future author’s mother, the widowed and impoverished Eliza Hodgson, accepted her brother’s offer to move to Tennessee, where (he claimed) he was prospering. Mrs. Hodgson took her children and sailed across the Atlantic. Soon fourteen-year-old Fanny—along with two brothers and two sisters—found herself in the Civil War South, in what turned out to be merely a log cabin, where her mother’s brother earned a shady and not very successful living.

These sources fed my curiosity about Frances Hodgson Burnett—and I found some parallels between her life and my own. Like me, she lost her father at the age of three. Far more surprising was my discovery that we shared a landscape: I was a child in Cumberland County, Tennessee, in the 1960s; a century earlier this quintessentially English author had herself been a child in nearby Knoxville. I remember exclaiming aloud, when I read this biographical tidbit, “What? Knoxville?” In 1863, the future author’s mother, the widowed and impoverished Eliza Hodgson, accepted her brother’s offer to move to Tennessee, where (he claimed) he was prospering. Mrs. Hodgson took her children and sailed across the Atlantic. Soon fourteen-year-old Fanny—along with two brothers and two sisters—found herself in the Civil War South, in what turned out to be merely a log cabin, where her mother’s brother earned a shady and not very successful living.

There was no time for childhood. A bookish nature lover practically from birth, Fanny had always found pleasure in solitary time in gardens and woodland. But such leanings wouldn’t earn a living. She tried and failed at running a school for young ladies. She was eighteen when she sold her first story to Godey’s Lady’s Book and Magazine. In 1870 her mother died, but the younger Hodgsons kept the home they had established in Knoxville, a big house these expatriates dubbed Vagabondia. Fanny kept writing and gradually got rid of the nickname and became simply Frances, the name she had always preferred. She married Swan Burnett in 1873, and her first novel, That Lass o’ Lowrie’s, came out three years later. It was hugely successful. After more than a dozen novels for adults, she turned to a book aimed at children. In 1886 Little Lord Fauntleroy reached a vast new audience, became a household word in literary circles, and launched an international fad for dressing boys in velvet jackets with lace collars. She became so well known that the 1893 Chicago World’s Fair featured a display of her books.

In 1887 Burnett began yearly visits to England by sailing over to attend Queen Victoria’s Jubilee celebrations. Gradually she spent more and more time in England and Europe. Her elder son died of consumption in Paris in 1890, which greatly influenced her compassionate view of life. Four years later, her younger son became gravely ill but survived. When he graduated from Harvard in 1898, Burnett divorced her dissolute and neglectful husband and returned to England. Soon she leased the grand estate of Great Maytham Hall, near Rolvenden in Kent, where the beautiful walled gardens helped inspire the novel for which she is now best remembered. (When Burnett died in 1924, her many eulogists praised Little Lord Fauntleroy, The Little Princess, and her other books. Most ignored The Secret Garden, which was still little known.)

In the autumn of 1910, The Secret Garden began serialization in The American Magazine, a venerable monthly aimed at adults, not children. It first appeared as a complete novel the next year. Burnett’s original title was Mistress Mary, from the nursery rhyme. In the early chapters, poor Mary is so self-centered and disagreeable that a little boy at her first temporary lodging after India gives her a nickname from the old nursery rhyme. Dancing around her and making faces, he chants: “Mistress Mary, quite contrary, How does your garden grow? With silver bells, and cockle shells, And marigolds all in a row.” Appropriately in a children’s book, Burnett ignored the many theories of the origin of the poem’s garden symbolism (Mary Stuart’s Tudor garden? A satire on Catholicism?) and concentrated on the reality of the garden itself—a site in which she could celebrate her own quirky brand of nature worship and her dogged brand of garden-loving, birdwatching, mystically-inclined positive thinking.

In the autumn of 1910, The Secret Garden began serialization in The American Magazine, a venerable monthly aimed at adults, not children. It first appeared as a complete novel the next year. Burnett’s original title was Mistress Mary, from the nursery rhyme. In the early chapters, poor Mary is so self-centered and disagreeable that a little boy at her first temporary lodging after India gives her a nickname from the old nursery rhyme. Dancing around her and making faces, he chants: “Mistress Mary, quite contrary, How does your garden grow? With silver bells, and cockle shells, And marigolds all in a row.” Appropriately in a children’s book, Burnett ignored the many theories of the origin of the poem’s garden symbolism (Mary Stuart’s Tudor garden? A satire on Catholicism?) and concentrated on the reality of the garden itself—a site in which she could celebrate her own quirky brand of nature worship and her dogged brand of garden-loving, birdwatching, mystically-inclined positive thinking.

In my childhood, the world seemed to me infinitely rich and diverse, clamoring for attention, filling my days like a combination of museum and parade. It still strikes me that way. As a boy, spending a lot of time outdoors in the one-acre lot between our house and our Uncle Bud’s and Aunt Matt’s next door, and gradually exploring farther into the more-than-hundred-acre wood behind the house, back to the climbing tree and the abandoned sandstone quarry and the hidden forest cemetery, socializing with owls and rabbits, luna moths and painted turtles, I felt the way Colin feels in the novel, as he considers how much he has learned from his new friends: “Ants’ ways, beetles’ ways, bees’ ways, frogs’ ways, birds’ ways, plants’ ways, gave him a new world to explore and when Dickon revealed them all and added foxes’ ways, otters’ ways, ferrets’ ways, squirrels’ ways, and trout’s and water-rats’ and badgers’ ways, there was no end to the things to talk about and think over.” This kind of response to the natural world seemed normal to me, requisite, inevitable. Learning people’s ways, other children’s ways, family’s ways—those took me longer. Literature helped. The Secret Garden helped. I was already in the garden; I grew up there. Burnett’s novel only took me back.

Copyright (c) 2011 by Michael Sims. All rights reserved. Sims’s new book is The Story of Charlotte’s Web: E. B. White’s Eccentric Life in Nature and the Birth of a Children’s Classic.