Funny Business

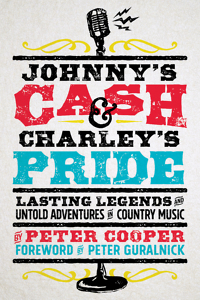

Peter Cooper writes of secrets, legends, and laughs in Johnny’s Cash & Charley’s Pride

It’s hard to believe that journalist Peter Cooper isn’t a lifelong Nashvillian. For fifteen years Cooper was a prolific and influential music writer for The Tennessean before joining the Country Music Hall of Fame and Museum, where he now serves as senior director, writer, and producer. He is also a Grammy-nominated songwriter whose work has been recorded by John Prine, Bobby Bare, and others. Cooper is so integrated with the city’s music scene that it seems like he arrived on a midnight train with Ernest Tubb in 1945, or maybe hitched a ride with Kris Kristofferson in 1967.

In fact, he showed up in 2000, less than two decades ago, after beginning his writing career in Spartanburg, South Carolina. At age twenty-two, he filled in for an English professor who had been assigned to review a Guy Clark show. “So off I went to write about whether or not Guy Clark—already a legendary songwriter in his fifties, known for remarkable emotional specificity and clarity of language—was any good,” Cooper recalls in his new book, Johnny’s Cash & Charley’s Pride: Lasting Legends and Untold Adventures in Country Music. “Hey, free ticket.”

In fact, he showed up in 2000, less than two decades ago, after beginning his writing career in Spartanburg, South Carolina. At age twenty-two, he filled in for an English professor who had been assigned to review a Guy Clark show. “So off I went to write about whether or not Guy Clark—already a legendary songwriter in his fifties, known for remarkable emotional specificity and clarity of language—was any good,” Cooper recalls in his new book, Johnny’s Cash & Charley’s Pride: Lasting Legends and Untold Adventures in Country Music. “Hey, free ticket.”

Halfway through the show, an overcome fan shouted, not once but three times, “I wish Guy Clark was my daddy.” In writing his review, Cooper decided to lead with that fan: “I was writing about connection, longing, regret, and pain,” he writes. “I was doing so with a chuckle line, but it was a chuckle line that got to something deeper.”

Cooper has followed that strategy ever since, with pretty much anyone who is anyone in country music. Stories of his meeting with Johnny Cash, visits with Merle Haggard and Loretta Lynn, and writing the message on George Jones’s gravestone in 2013 make Johnny’s Cash & Charley’s Pride resonate with humor and depth. The writing is often so funny it could be catalogued simply as humor, but Cooper’s delivery is reminiscent of Mark Twain’s: at just the moment you’re laughing so hard you spill a little beer on the bar, he slips in a phrase or word that freezes you in place.

In that first piece on Guy Clark, Cooper described an artist who could “stand on a stage, sing a song called ‘Desperadoes Waiting on a Train,’ and make grown men weep over the tyranny of lineage.” Through countless articles since then, Cooper has become for country what Lester Bangs was for rock: not only a critic but also a storyteller of events both witnessed and experienced. He is on the scene for the rest of us, serving as touchstone for what is real and what is nonsense.

Here’s Cooper on Taylor Swift bringing him home-baked cookies as he interviewed her early in her rise to stardom: “Taylor Swift had become a resounding commercial force simply by doing what no one else had done, which was, simply, being Taylor Swift. To sit down face-to-face with a 19-year-old Swift was to comprehend that she was someone of uncommon intellect, palpable presence, and perfectly risen cookies.”

Here’s Cooper on Taylor Swift bringing him home-baked cookies as he interviewed her early in her rise to stardom: “Taylor Swift had become a resounding commercial force simply by doing what no one else had done, which was, simply, being Taylor Swift. To sit down face-to-face with a 19-year-old Swift was to comprehend that she was someone of uncommon intellect, palpable presence, and perfectly risen cookies.”

The book contains more than tales of recent superstars: Cooper also personalizes the history of country music by finding its echoes in contemporary music. The “Carter scratch”—a guitar method first recorded in Bristol, Tennessee, in 1927—he says, “is the basis for the way most acoustic guitarists today approach the instrument, whether or not they’ve ever heard of Mother Maybelle Carter.” He explains how a tonsillectomy early in Ernest Tubb’s career ruined his ability to do a Jimmie Rodgers yodel but gave Tubb a gravelly voice which, when combined with electrically amplified instruments, produced what later generations think of as country music.

Johnny’s Cash & Charley’s Pride includes the rules for songwriters created by Cowboy Jack Clement (who wrote the lyrics from which the book’s title is taken): “Remember, boys, we’re in the fun business. If we’re not having fun, we’re not doing our jobs.”

While such gems appear on practically every page, the book is not entirely about music. Some of Cooper’s most quotable lessons pertain to other kinds of writing. “Let me tell you what I learned in journalism school,” he begins a chapter on storytelling. “Nothing. Didn’t go. Didn’t take a class. But I’m told part of what is taught, and I’ve heard editors mention this, is that we must be objective.” Objectivity did not take with Peter Cooper. Objectivity is dispassionate, he writes, but “we are in the passion business.” Then he delivers wisdom for any writer seeking to leave a mark:

“If you write exactly what you feel, you have written an exclusive.

“If you write something objective, you have most likely written a measured mediocrity.”

Peter Cooper writes on the same level as a good country song. He makes you feel that you have not only seen the legends he writes about relaxing backstage, but had drinks and cookies with them, too, and laughed at life with them, and cried and cried and cried.

Michael Ray Taylor teaches journalism at Henderson State University in Arkadelphia, Arkansas. He is the author of several books of nonfiction and coauthor of a textbook, Creating Comics as Journalism, Memoir and Nonfiction.