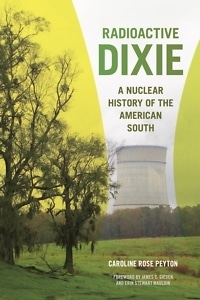

Going Nuclear

Caroline Peyton weighs the promises and perils of nuclear power plants in the South

The rural town of Hartsville, Tennessee, was in the news this past September when the Tennessee Valley Authority demolished a 500-foot concrete tube that locals derided as a “used beer can.” In 1973, TVA touted the building of the “world’s largest nuclear plant,” and this large structure was one of its cooling towers. But the plant was never completed. In Radioactive Dixie, Caroline Rose Peyton weaves the Hartsville story into a wider exploration of the promise and perils of nuclear power in the South, the U.S. region with the most nuclear reactors — and the most radioactive waste.

Peyton is an associate professor of teaching at the University of Memphis. Her scholarship has won the Alice Hamilton Prize from the American Society for Environmental History and the Jack Temple Kirby Prize from the Southern Historical Association. She answered questions via email from Chapter 16:

Chapter 16: How did Southern politicians cast the building of nuclear power sites in their region? Did it fit into the vision of a “New South”?

Caroline Peyton: From the 1940s to the 1960s, politicians in the South cast nuclear projects, whether commercial, military, or research related, as a positive good. There were real, tangible benefits to many of these sites: jobs, federal dollars, and institution building. Universities in the South benefited; scientists and engineers from both within the region and outside it came to Southern institutions and nuclear facilities as a result. Nuclear power promised cheap, plentiful energy, which had been one critical component to a century-long vision of the New South. They saw a tremendous opportunity.

Later, as the politics surrounding radioactive waste, nuclear power, and weapons became more charged, some politicians in the South openly weighed the pros and cons, while others defended it tooth and nail. The straightforward boosterism of the past became more complicated and more politically polarized.

Chapter 16: Southern historians have devoted much attention to the region’s legacies of racial oppression and rural poverty. Do those themes intersect with the South’s nuclear history?

Peyton: Absolutely. While I would argue there’s no clear-cut pattern, out of necessity for siting, you do see many nuclear facilities in rural places. Some of those places have been shaped by poverty (others less so) and race. Understandably, communities eagerly sought the benefits that a nuclear power plant could produce, while also questioning a commitment to safety and to a just distribution of benefits, if they bore the most immediate risks of living near nuclear sites. History informed how people understood the opportunities and the risks a nuclear project might bring to their communities.

Also, many of these projects were underway in the 1960s and 1970s when the South was undergoing a seismic shift socially, politically, and culturally. The debates over the nuclear industry were thrust into the middle of a turbulent time, both regionally and nationally.

Chapter 16: Some of the most vivid passages in Radioactive Dixie are your personal descriptions of nuclear sites, based on your travels throughout the South. What did you learn from visiting these sites?

Peyton: You learn the importance of place, and why people in the past felt certain ways about nuclear projects — both good and bad. When I traveled to Hartsville, Tom P. Thompson Jr. and Faith Young both invited me into their homes. Michael Benjamin gave me a tour of the Barnwell LLW site [in South Carolina], which was extremely important. Plus, I’ve mostly been a city slicker in the South, but rural places have always interested me. My initial introduction to the nuclear South was through a field trip to Oak Ridge as a kid. This project opened my eyes to the lesser-known communities that dot our region and their histories.

Chapter 16: “South Carolina is not a garbage can for the rest of the United States!” exclaimed one angry constituent amid plans for a nuclear waste disposal site there. How did nuclear facilities serve as sites of political activism? What were the concerns, language, and tactics of those fearing a “radioactive Dixie”?

Peyton: Nuclear facilities in the 1970s and 1980s were hotspots for political activism across the globe. Anti-nuclear activism, which stretched from protests opposing commercial nuclear power to nuclear weapons production, clearly built upon the anti-war movement, the Civil Rights Movement, and the environmental movement. Quite frankly, it was a paranoid time anyway. These big projects required lots of governmental oversight at a moment when no one trusted the authorities. People feared accidents, environmental contamination, and nuclear war. The apparatus designed to regulate the nuclear industry was in a period of overhaul during the 1970s and 1980s.

Peyton: Nuclear facilities in the 1970s and 1980s were hotspots for political activism across the globe. Anti-nuclear activism, which stretched from protests opposing commercial nuclear power to nuclear weapons production, clearly built upon the anti-war movement, the Civil Rights Movement, and the environmental movement. Quite frankly, it was a paranoid time anyway. These big projects required lots of governmental oversight at a moment when no one trusted the authorities. People feared accidents, environmental contamination, and nuclear war. The apparatus designed to regulate the nuclear industry was in a period of overhaul during the 1970s and 1980s.

Activists in the South saw the region as bearing a greater burden than other places. It was fascinating to see anti-nuclear groups conjure up comparisons to Pripyat, Ukraine, which was abandoned after the Chernobyl accident, and place their fears in regional terms, i.e., the new Southern burden of sorts.

Chapter 16: What happened in Hartsville, Tennessee? Why was that massive “used beer can” built? Why did it never become part of the “world’s largest nuclear plant”?

Peyton: The Tennessee Valley Authority was at the forefront of the South’s commercial nuclear power expansion. It planned to build a nuclear power plant in Hartsville and had plans for a number of other nuclear power facilities elsewhere. The 1970s were not kind to the nuclear industry, in part because of anti-nuclear activism, but also because the economic downturn hit these projects hard. There were skyrocketing costs, delays, greater regulatory interventions, and internal problems.

In Hartsville, construction started on the plant, and then TVA made the difficult decision to cancel the project. Hartsville’s story tells us a lot about the nuclear-building spree, which picked up in the 1960s, and the fallout that happened in the late 1970s and early 1980s. Of course, now, we’re entering an interesting period where modular reactors and nuclear power generally have reentered the conversation, and rightly so. History can serve as a useful guide for the future of nuclear power.

Aram Goudsouzian is the Bizot Family Professor of History at the University of Memphis. His most recent book is The Men and the Moment: The Election of 1968 and the Rise of Partisan Politics in America.