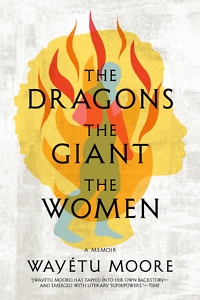

Here Be Dragons

Wayétu Moore flees from Liberia’s civil war and fights to be seen in race-obsessed America

In the first chapter of Wayétu Moore’s memoir, The Dragons, the Giant, the Women, it’s Moore’s fifth birthday. “Tutu,” as her family calls her, wears a purple linen dress for the party and begs to help wash collard greens. “In those years, turning five tasted like Tang powder on the porch after supper,” Moore writes. But her mother Mam’s absence adds a bitter note. Again and again, Tutu asks the adults when she can visit New York, where Mam is studying as a Fulbright scholar. “Why would you want to go there, you girl?” they answer, reassuring her that “Liberia’s sweetness was incomparable,” sweeter than mango, milk candy, sugar bread, or America — “none a match for the taste then, of my country.”

The word “then” quietly underlines the portent overshadowing an ordinary day in their Monrovia neighborhood, where boys go fishing with their “Ol’ Pas” — grandfathers — on the Atlantic shore, girls fetch water from a well, and elders gossip about the corrupt president, Samuel Doe, and a potential usurper they refer to as “Charles.” Tutu’s little-girl imagination renders doomed President Doe as a monster from her nightmares — Hawa Undu, an avenging hero-prince who becomes the bloodthirsty dragons he’d promised to slay:

And now, Hawa Undu was president of Liberia, once a prince with good intentions. Ol’ Ma said everyone was talking about him because there was another prince who wanted to enter the forest and kill Hawa Undu, to restore peace. This prince was named Charles, like my Ol’ Pa. Some thought he would be the real thing — that he could kill Hawa Undu and put an end to the haunting of the forest and the spirit princes who danced throughout — but others feared he would be the same, that no prince could enter the forest and keep his intentions. The woods will blind, will blunder. Hawa Undu would never die.

Charles, of course, is the now-infamous war criminal Charles Taylor, so we know where this story is going. The sweetness of ordinary days in Liberia will soon be despoiled, and so will Tutu’s childhood.

The war comes for the Moore family on a Saturday, when Tutu is watching The Sound of Music on a VCR with her grandmother, Ol’ Ma. Tutu and her two sisters flee on foot with their father and Ol’ Ma to the soundtrack of “Edelweiss” fading behind them and screams and staccato gunfire drawing nearer in the streets. As the family walks for weeks through forests, hiding out in shattered houses, the adults try to shield the girls from the starkest horrors by explaining away the gunshots as drums and the dead as people sleeping. Tutu’s magical thinking transforms her tall papa into a giant who grows larger in her eyes every time he braves another rebel checkpoint, where executions are routine.

The family takes shelter in Ol’ Ma’s home village, the coil of hunger and violence tightening, with no contact with anyone in the outside world — including Mam. And then one day a female rebel soldier appears, sent by Mam to spirit them across the border to safety.

The story skips to Moore the young woman, a burgeoning writer in New York who is suffering from PTSD and bewildered by her adopted home, where the color of her skin is apparently a defining trait. She recalls brushes with racism and isolation as a schoolgirl struggling to adapt to life as an immigrant in Connecticut, then Texas. (The family also lived in Memphis briefly.) Moore’s thoughts and dreams linger on two women: the family’s mysterious savior, named “Satta,” and Mam, whose absence at such a traumatic time in Tutu’s life has carved a scar into Moore’s psyche. Those ruminations lead Moore back to Liberia, where she hopes to find Satta and bridge the chasm between herself and Mam, who has returned to Liberia with Moore’s father.

The story skips to Moore the young woman, a burgeoning writer in New York who is suffering from PTSD and bewildered by her adopted home, where the color of her skin is apparently a defining trait. She recalls brushes with racism and isolation as a schoolgirl struggling to adapt to life as an immigrant in Connecticut, then Texas. (The family also lived in Memphis briefly.) Moore’s thoughts and dreams linger on two women: the family’s mysterious savior, named “Satta,” and Mam, whose absence at such a traumatic time in Tutu’s life has carved a scar into Moore’s psyche. Those ruminations lead Moore back to Liberia, where she hopes to find Satta and bridge the chasm between herself and Mam, who has returned to Liberia with Moore’s father.

Moore begins to close that distance by offering Mam’s side of the story: her ambivalence about leaving the family for New York, her anguish when the war severs contact, and then her determination to get them out. It’s not a spoiler to say that Mam’s daring plan succeeded — we understand from the outset that Moore’s immediate family survived to tell this tale. But knowing the outcome doesn’t diminish the suspense of their escape. In the final pages, Moore brings 5-year-old Tutu back to narrate the reunion with Mam. Told in spare, childlike prose, the scene is vivid and heart shattering. (Full disclosure: When I read that section aloud to my husband, we both cried.)

Moore’s gorgeously rendered memoir is an exhortation not to surrender to tragedy fatigue. There are so many stories of war and forced migration that they may, at a distance, blur into sameness — the dismal refrain of tyrants destroying their societies with violence, the dragon that never dies. But zoom in and those abstractions sharpen into singular stories, each one a complicated blend of loss and salvation, tragedy and triumph, bitterness and wisdom. “There are many stories of war to tell. You will hear them all,” writes Moore. “But remember among those who were lost, some made it through. Among the dragons there will always be heroes.”

Kim Green is a Nashville writer and public radio producer, a licensed pilot and flight instructor, and the editor of PursuitMag, a magazine for private investigators.