How Country Grew Up

Geoffrey Himes describes the marriage of country music and modern sensibilities

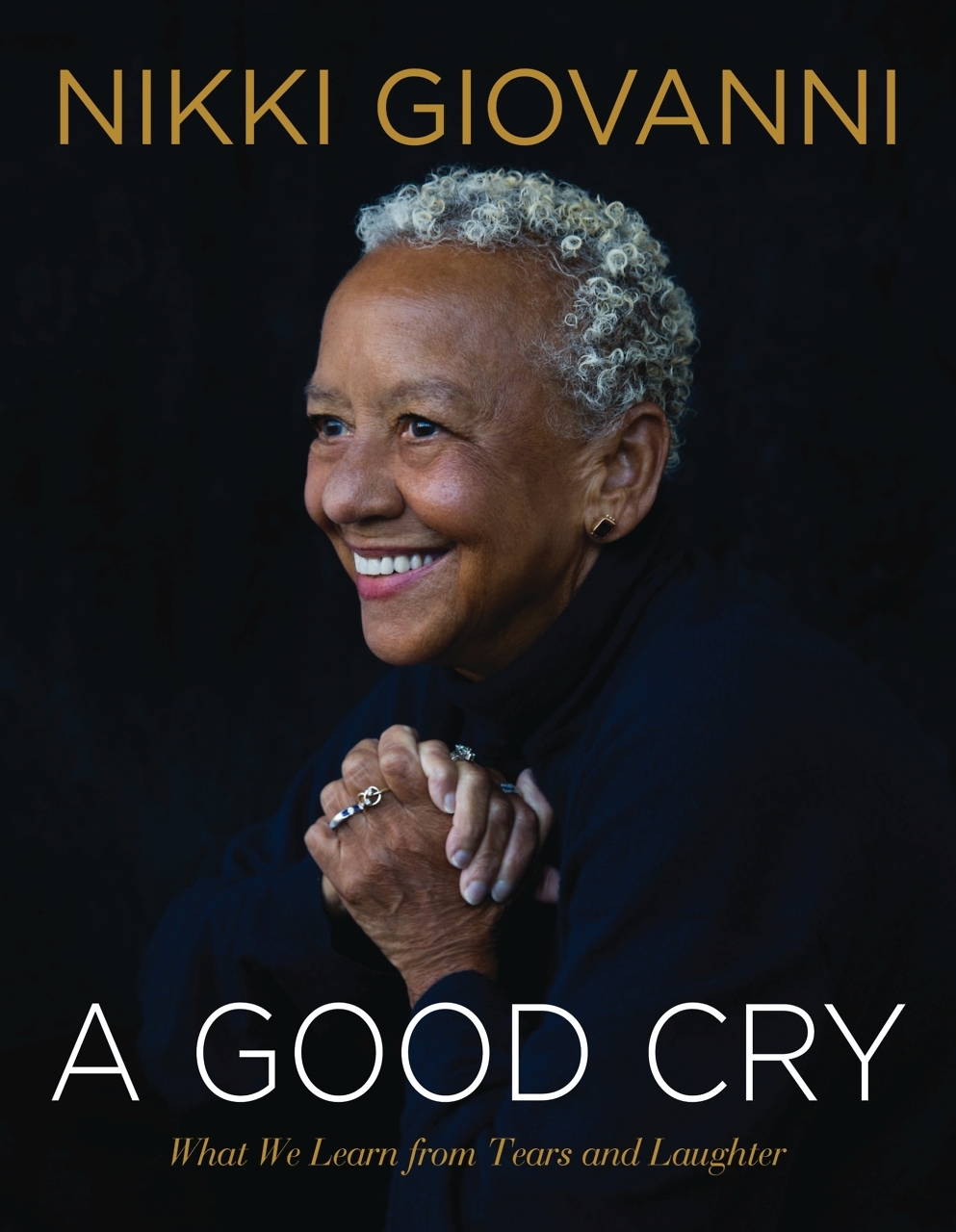

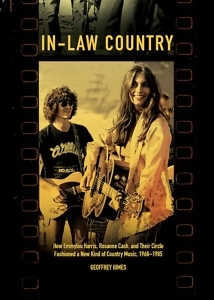

The conceit of Geoffrey Himes’ In-Law Country: How Emmylou Harris, Rosanne Cash, and Their Circle Fashioned a New Kind of Country Music, 1968-1985 is that a group of ambitious country and pop musicians found a way to make country even more adult than it had been previously.

For Himes — a longtime music journalist with several previous books to his credit — the work Cash, Harris, and a group of songwriters, dissidents, and record producers released from 1979 to 1985 was about the changing face of marriage itself. The music came out of complex relationships between Harris and Cash and their husbands, a group that at one time included Rodney Crowell and producer Brian Ahern. In-Law Country looks at how country embraced modernism a decade after the rest of the pop music world had internalized the achievements of The Beatles and Bob Dylan.

For Himes — a longtime music journalist with several previous books to his credit — the work Cash, Harris, and a group of songwriters, dissidents, and record producers released from 1979 to 1985 was about the changing face of marriage itself. The music came out of complex relationships between Harris and Cash and their husbands, a group that at one time included Rodney Crowell and producer Brian Ahern. In-Law Country looks at how country embraced modernism a decade after the rest of the pop music world had internalized the achievements of The Beatles and Bob Dylan.

Nashville in the early ‘70s had begun adjusting to the world of rock, inspired by Dylan’s epochal 1966 Blonde on Blonde sessions, recorded with some of the city’s finest session musicians. Still, country music in the mid-70s was a tangle of contradictions. On the one hand, a loosely organized collection of singer-songwriters who heard Dylan and never looked back began providing material for mainstream country artists. By the early ‘80s, Guy Clark — one of the high priests of minimalist Texas songwriting — was enjoying hits sung by other people. Kentucky-born mandolin player and singer Ricky Skaggs took Clark’s “Heartbroke” to the top of the country charts in 1983 after changing the lyrics to suit his sensibility.

For Himes, the relationship between Rosanne Cash and her father, Johnny Cash, symbolizes how country musicians of different generations shared values even when those values — shaped in the messy post-Beatles reality of the ‘60s — tended to grate against the old ways. Himes correctly sees The Byrds’ 1968 album Sweetheart of the Rodeo as an early example of irony in country music, and he makes the distinction between country’s local irony and the existential irony The Beatles and virtually every important rock band of the decade indulged in.

More generally, songwriting had changed in the ‘60s, with John Lennon and Paul McCartney coexisting with John Hartford, Harlan Howard, and many other country-adjacent tunesmiths who were reacting to the new world of pop. Himes does a superb job of integrating interviews and commentary on Clark, Townes Van Zandt, Crowell, and Gram Parsons into his narrative, and all of these songwriters pushed country into new territory.

Himes is sharp in his descriptions of country rock, and its descendent “In-Law Country,” and he understands how Cash and Harris drew upon rock — and even the new wave music of the era — to create a fresh take on the genre. He somewhat underrates the best country-rock record, The Flying Burrito Brothers’ 1969 The Gilded Palace of Sin. “As good as the vocals and songwriting were, the instrumental backing was a shambles, often losing the groove and awkwardly mixing sweet picking with distorted guitar.” The Gilded Palace of Sin isn’t a country record — it’s a record, with the electric guitars and tense pedal-steel licks an essential part of an album that defies category. Certainly, Chris Hillman’s bass parts on Gilded are more rubbery than anything a Nashville session musician would’ve played in 1969.

Himes’ take on Parsons, whose meager recorded output includes a couple of Flying Burrito Brothers albums and two solo albums that feature Harris’ harmony singing, serves his thesis that what made In-Law Country different from older country was a production savvy that eluded Parsons. He recounts the career of Canadian-born producer Brian Ahern, who began making hits with Anne Murray before producing, and marrying, Harris. In every way, Ahern’s production is an advance over the standard Nashville approach.

Ahern produced Harris’ 1975 album Pieces of the Sky and would produce many of her records through 2008’s All I Intended to Be. Similarly, Rodney Crowell, who had grown up in Houston, Texas, would produce albums by his wife, Rosanne Cash. As a songwriter, singer, and producer, Crowell remains a huge figure in country music — a first-rate bandleader and conceptualist.

The albums and singles Harris and Cash released in the ‘80s stand as a compendium of great country singing. Harris came to country from the folk world, and her singing is a mixture of folk and country disciplines. For Cash, singing came less naturally, but it’s hard to conceive of a more nuanced vocal on any pop or country record than her rendition of her song “Seven Year Ache,” released in 1981.

In-Law Country is an exhaustive look at how country grew up in the ‘80s during a time when all former rules of pop music had gone out the window. Harris, Cash, and Clark all sang and wrote about real life, and that’s a subject that deserves its own musical style.

Edd Hurt is a writer and musician in Nashville. He’s written about music for Nashville Scene, American Songwriter, No Depression, The Village Voice, and other publications. He produced and played keyboards on The Contact Group’s 2021 album of 1970s covers, Varnished Suffrages.