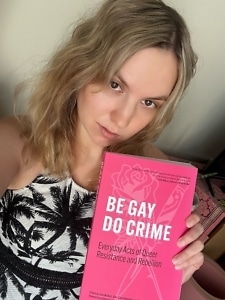

Many Visions of Liberation

Be Gay, Do Crime is a daily history of queer resistance and resilience

The LGBTQ+ community has always struggled for respect, acceptance, and safety in the face of a hostile society, but the struggle has been marked by courageous, even joyful resistance and resilience. Be Gay, Do Crime surveys the long history of that resistance through a daily catalog of notable events.

In this carefully annotated volume, editors Zane McNeill, Riley Clare Valentine, and Blu Buchanan take us from January 1 (the date in 1962 when Illinois became the first state to repeal its “crimes against nature” statute) to December 31 (when, in 1918, openly lesbian labor activist Marie Equi was convicted of sedition for criticizing corporate profiteering from the U.S. war effort).

McNeill, whose previous books include Y’all Means All and Deviant Hollers, answered questions about Be Gay, Do Crime by email.

Chapter 16: This book required a massive data-gathering effort. What did you learn that surprised you in that process?

Zane McNeill: I was surprised by how much of gay history is difficult to organize and verify by specific dates. This makes sense, though, because “gay history,” like much of history, is often represented by the wealthy and elite — those most likely to make it into the archive and have their history written down. Radical queer history, on the other hand, is usually less studied, less documented, and often excluded from the official “gay history” archive. With this book, we tried our best to include as much counter and radical queer history as possible, while still ensuring the information could be verified. For example, many gay history books mention certain events and cite the month and year they occurred, but not the exact date. Since this book is an “every day in queer history” project, we excluded most events that could not be tied to a specific day.

That led to another surprise: queer organizers are very busy for Pride month (there were far more radical queer moments than we could include for each day in June), but it was much harder to find queer events that occurred on every day in the winter months. To make sure every day was covered, we sometimes had to dig deep, occasionally relying on events we might not otherwise have included — such as dates tied to BDSM and gay leather communities — which was really rewarding. I’m glad it pushed us out of our comfort zone and challenged what we considered constituting ‘resistance’ histories.

Chapter 16: Which of the book’s entries do you find especially fascinating or empowering?

McNeill: Before researching for this book, I hadn’t realized how much of the labor victories we usually credit to Franklin D. Roosevelt (FDR) were in fact shaped by Eleanor Roosevelt and her circle of lesbian friends. For example, Frances Perkins was Secretary of Labor from 1933 to 1945 and a central architect of the New Deal. She lived with and shared a very close, loving relationship with Mary Harriman Rumsey, who was the founder of the Junior League for the Promotion of Settlement Movements, from 1933 until Rumsey’s death in 1934. The two were also friends of Eleanor Roosevelt. Likewise, labor organizer Rose Schneiderman was close friends with Roosevelt, which contributed to her being appointed by FDR to the National Recovery Administration’s Labor Advisory Board in 1933. Schneiderman had a long partnership with Maud O’Farrell Swartz, who served as president of the Women’s Trade Union League from 1922 to 1926.

This is just one example of many in the book that show how queer history has been eclipsed and, in many ways, rewritten from a cisgender and patriarchal perspective. By recovering and reexamining these histories, we gain a profoundly different understanding of the past — as well as a better understanding of our current political moment.

Chapter 16: You urge readers not to read the book alone but to share it in community with others. Do you have particular suggestions for what that might look like?

McNeill: In this moment, it has become very clear that the far right wants to eradicate transgender and queer people’s joy, community, and safety. In September, Donald Trump escalated his attack on LGBTQ communities by signing a national security directive identifying “extremism on gender,” “anti-capitalism,” and “hostility towards those who hold traditional American views on family” as indicators of violence. This, along with the previous executive order he signed labeling “antifa” a domestic terrorism organization, is meant to chill nonprofit organization and push LGBTQ people back into the closet.

McNeill: In this moment, it has become very clear that the far right wants to eradicate transgender and queer people’s joy, community, and safety. In September, Donald Trump escalated his attack on LGBTQ communities by signing a national security directive identifying “extremism on gender,” “anti-capitalism,” and “hostility towards those who hold traditional American views on family” as indicators of violence. This, along with the previous executive order he signed labeling “antifa” a domestic terrorism organization, is meant to chill nonprofit organization and push LGBTQ people back into the closet.

Since the book has been published, we have faced harassment from far-right influencers including Libs of Tik Tok and Catturd. Libs of TikTok has said that a flier publicizing a book talk for Be Gay, Do Crime is “a symbol of lgbtq t*rrorism” and called us the “lgbtq militia.” Their followers have said that we are part of a “transgender cult” that is pushing “propaganda [that] is radicalizing youth.” We have been told this book is evidence of “promoting violence” and “criminal.” Commenters tagged the FBI and the DOJ, the same groups tasked by Donald Trump to continue the history of the federal government surveilling, pathologizing, and criminalizing LGBTQ people.

I say all of this to show how scary it is right now to be queer and trans. There is an increasing risk in being openly queer, reading queer books, and creating queer spaces. But that is why it is so important to do just that. Being openly queer and/or transgender is resistance. Reading this book is resistance. Showing this book to others, especially young people who are especially targeted by anti-LGBTQ laws, is resistance. It is so important for trans and queer youth to know that there is nothing wrong with them, that they are not alone, and that they come from a long lineage of rabblerousers who fought to create a world where they could be safely themselves.

Learning from our history in community with others terrifies the far right. Fascists get power from making us small and scared — too scared to read, to dream, to live. But they are the ones who are so scared of us and our power and our joy. Refusing to be silent and invisible greatly weakens them. That is why I ask y’all to read this book together in book clubs, bring it to your local outdoor library, and leave it at queer coffeeshops and LGBTQ centers.

Chapter 16: The LGBTQ+ community has long been targeted by the political right, with attacks on trans rights being especially fierce recently. But you also point to tensions or conflicts between different segments of the community. How can Be Gay, Do Crime help people better understand and navigate those conflicts?

McNeill: So much of LGBTQ history tends to focus on white, wealthy, able-bodied cisgender men. In practice, this usually means centering the experiences of white gay men and celebrating their “success” in assimilating into dominant American culture and securing certain legal rights. But this kind of history — framed around linear progress and assimilation — leaves out much of queer history. It overlooks the fact that ideas of “success” vary and that respectability politics often exclude or abandon large parts of the queer community.

In this book, we try to highlight the many different visions of what liberation has meant. For example, the Mattachine Society began in the 1950s with a radical critique of mainstream society, but soon shifted toward a politics of respectability and acceptance within dominant culture. Frustration with these assimilationist tactics helped give rise to more radical groups such as the Gay Liberation Front and the Queens Liberation Front, which demanded broader structural change and greater inclusion of drag and trans communities.

These tensions over tactics and goals — particularly over who is included in a group’s vision of liberation and who is left behind — have continued to surface within LGBTQ spaces. Queer activists have at times directly challenged other LGBTQ organizations, as seen with the Black Pride 4 at Columbus Pride in 2017, No Justice No Pride at DC Pride in 2017, and Black Lives Matter–Toronto organizers who halted Toronto Pride in 2016.

We sought to include as many of these groups, protests, and conflicts as possible so that readers can learn from the past — both from tactics that proved successful and from those that fell short.

Chapter 16: The title is described as “provocative and playful,” and the book is filled with stories of resilience and resistance. But the stakes for LGBTQ+ people have always been high and are likely to remain so in the foreseeable future. How do folks hang onto joy?

McNeill: Joy itself is an act of resistance, demonstrating the resilience and ungovernability of queer and trans people despite state surveillance, criminalization, and pathologization. Many entries in this book document the state’s attempts to crush queer and trans joy.

Police raids of William Dorsey Swann’s birthday drag ball in 1888, Eve’s Hangout in 1926, the Tay-Bush Inn in 1961, The Patch Bar in 1968, the Snake Pit in 1970, “Operation Soap” in 1981, the Glad Day Bookshop in 1982, Club Toronto’s Pussy Palace in 2000, and raids on gay leather bars in Seattle in 2024 show the state has long been threatened by queer and trans joy.

Yet despite such targeting, queer and trans people continue to carve out community and resist police violence. They protested each of these raids and the arrests that followed, showing up to confront the state in defense of their communities. This act of standing together is an expression of love. Every moment of protest documented in this book is also a moment of joy — because queer and trans people organizing, engaging in community defense, and fighting for liberation embody joy itself.

These moments remind me that we must show up for one another more than ever and refuse to let the state harm our friends, our lovers, and our families. We must also continue to create spaces of joy — joy in our bodies, joy in our relationships, and joy in communities where everyone is fed, housed, safe, and loved.

Chapter 16: What books on queer history do you recommend to readers who want to learn more?

McNeill: My favorite queer nonfiction books are That’s Revolting!: Queer Strategies for Resisting Assimilation (Soft Skull Press, 2004), Against Equality: Queer Revolution, Not Mere Inclusion (AK Press, 2004), and Black on Both Sides: A Racial History of Trans Identity (University of Minnesota Press, 2017).

I would also recommend anything (and everything) by Hugh Ryan, Susan Stryker, Michael Bronski, John D’Emilio, Eric Marcus, Marc Stein, Jonathan Katz, Urvashi Vaid, Emily K. Hobson, Karma Chávez, Eric Stanley, Evelyn Blackwood, Shuli Branson, Eli Elrick, and Jack Halberstam.

Maria Browning is a fifth-generation Tennessean who grew up in Erin and Nashville. Her work has appeared in Guernica, Los Angeles Review of Books, Literary Hub, and The New York Times. She’s the editor of Chapter 16.