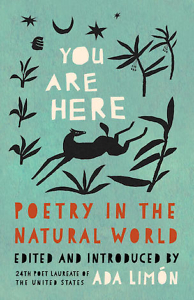

Not a Place to Visit

Reflections on You Are Here, a collection of contemporary nature poetry

In her introduction to You Are Here: Poetry in the Natural World, U.S. Poet Laureate Ada Limón describes the trees seen from her window: the magnolia, the hackberry, “and the old mulberry tree that drapes its tired branches over everything like it wants to give up but won’t.”

“Watching them,” she writes “makes me feel at once more human and less human. I become aware that I am in a body, yes, but it is a body connected to these trees, and we are breathing together.” Limón is a graceful and fierce poet herself, but beyond the introduction, readers won’t find her words in this collection. Instead, she commissioned 50 American poets to reflect on their unique place in the world, wherever they are and however they see it. As Librarian of Congress Carla Hayden explains in her foreword, “While these poems emerge from deeply personal perspectives, together they reveal that nature, like poetry, is universal — and that our interpretations of the natural world are grounded in the nature of our humanity.”

“Watching them,” she writes “makes me feel at once more human and less human. I become aware that I am in a body, yes, but it is a body connected to these trees, and we are breathing together.” Limón is a graceful and fierce poet herself, but beyond the introduction, readers won’t find her words in this collection. Instead, she commissioned 50 American poets to reflect on their unique place in the world, wherever they are and however they see it. As Librarian of Congress Carla Hayden explains in her foreword, “While these poems emerge from deeply personal perspectives, together they reveal that nature, like poetry, is universal — and that our interpretations of the natural world are grounded in the nature of our humanity.”

***

I have not always been a person who embraces traditions. Doing a thing just because it has always been done leaves scant room for growth, making necessary adaptations to shifting circumstances even more difficult. But years ago, when my children were small, I decided we should commit to a New Year’s Day hike. Most years, even when it has been cold or unpleasant, we’ve spent part of that first day of the year outside, in the woods or by a stream, clambering over rock faces and allowing the quiet strength of the mountains to color our perspective on another year.

Our 2024 had an inauspicious start with an early morning car crash in our driveway, but after a few hours of police lights and insurance questions, we still put on our boots and made for a trailhead. My daughter was home after her first semester in college, and we walked together, sometimes chatting quietly, sometimes bending low to share our delight in a crawling creature. At the culmination of that trail is a waterfall, with a wooden platform for viewing, and there we found the following words, scrawled neatly in Sharpie: “You Are Here Now.”

I’m not one to endorse defacing public property, but on that chilly, damp morning, I needed to see those words. I needed to be reminded of every iteration of them, each word building on the next — You are. You are here. You are here now.

***

A few months later, as winter’s bare branches began to open the door to spring light and life, I read Limón’s introduction to her new collection, where she admits to rising anxiety over the various catastrophes of the day and recounts a similar moment of clarity at a trailhead:

As I stared at the trail map, I saw the friendly little red arrow that pointed to where I was on the map, its caption: You Are Here. It seemed not only to serve as a locator, but as a reminder that I was living right now, breathing in the woods, that there was life around me, that the natural world was right here and I was a part of it; I was nature too.

I knew that feeling, had grounded myself in that truth countless times over the years. I also knew those fears. I understood the way uncertainty creeps in uninvited, and I suspect this feeling is one we all recognize. Certainly the poets gathered in You Are Here would agree, as many of them grapple with racism or climate change, grief and loss in all its forms. But they also dwell fully in the good and the beautiful. Hayden explains, “Some of the poems included here contend with the destruction of nature, while others consider its abundance and resilience — and some do both at the same time.”

***

I read You Are Here again after almost three weeks of exploration in Iceland, a magical place far removed from anything I would call ordinary. I climbed mountains and shimmied down narrow ridges full of dust and gravel. I drove past dozens of breathtaking waterfalls before taking a moss-lined trail to yet another waterfall, each more astonishing than the one before. I removed layers of outerwear in an icy wind in order to sink into a hot river, naturally warmed by geothermal springs. And I walked through an ice cave on one of the largest glaciers in the world.

At every turn, I had to remind myself: You are here. Be here now. Don’t take one moment of this for granted. I was, as Limón puts it, “at once more human and less human.” As I considered the certain and speeding deterioration of the glaciers, I was deeply aware of the outsized impact of my choices, even those that brought me to this place of wonder. I was also made so small, reminded of my own insignificance in the face of such grandeur.

Perhaps my favorite poem from the collection is Jason Schneiderman’s “Staircase,” with its long prose-like line structure and its insistent questioning: “And oh my God, are you as exhausted / as I am from grieving the planet? Tell me what I’m supposed to say / about the end of the world. Tell me how not to be / hysterical every time / I see what’s coming.” It captures perfectly that uncertainty, the big one, the one that leaves me wondering just how many such hikes my daughter will get to enjoy, just what will happen to a place like Iceland when it no longer has a glacier to feed its abundant waterways.

Contrasting that gesture of despair, however, is hope. Hope that this world and its people will survive and continue to pour out their beauties. I love Ruth Awad’s “Reasons to Live,” especially its closing lines: “… and the rivers // will set their stones and ribbons / at your door if only // you’ll let the world / soften you with its touching.”

***

Limón sees You Are Here as “an offering” and an invitation, an extension of her Poetry in Parks project — seven unique installations at U.S. National Parks across the country, each a picnic table, each with an accompanying poem selected for that site. The Great Smoky Mountains National Park is home to one of these tables and features Lucille Clifton’s “the earth is a living thing.” It was Clifton, she asserts, who inspired her to write, attempting her first fumbling poems as a child after hearing Clifton read her work on a television program. Now, it is Limón’s turn to inspire, turning to the power of community and the natural world, asking visitors to the parks and readers of You Are Here to “consider making your own version of a ’You Are Here’ poem to grow alongside ours … so we may continue to flourish. I hope this anthology serves as a reminder that there is more time to plant trees, to write poems, to not just be in wonder at this planet, but to offer something back to it, to offer something back together. Because nature is not a place to visit. Nature is who we are.”

Sara Beth West is a school librarian and a freelance writer focusing on book reviews and author interviews. In addition to Chapter 16, publications include Shelf Awareness, BookPage, Southern Review of Books, and more. She lives in Chattanooga.