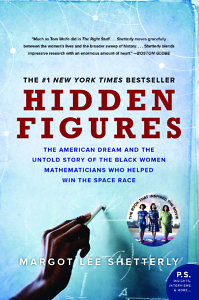

Part of the American Epic

Margot Lee Shetterly’s blockbuster Hidden Figures is this year’s Nashville Reads selection

Margot Lee Shetterly was raised in the shadow of NASA’s Langley Research Center in Hampton, Virginia, where her father was a climate scientist. It was never news to her that African- American scientists and engineers had always played an essential role in the agency’s achievements. She describes Hampton as a place where “the face of science was brown like mine.” But a 2010 visit to her hometown made her aware of how much of Langley’s history she didn’t know, sending her on a years-long investigation that ultimately produced Hidden Figures, her compelling, meticulously-researched story of the black women mathematicians, known as “computers,” who did critical work in the development of the U.S. aerospace program.

Hidden Figures opens during World War II, when the war effort created job opportunities for women—both black and white—with training in mathematics and engineering. Jim Crow segregation was still in full force in Virginia, however, and the black women who came to offer their knowledge in the nation’s service confronted a unique set of difficulties and indignities. By focusing on a few of the most prominent individuals to rise out of the segregated unit called West Computing, Shetterly maps the history of black women mathematicians at Langley through the post-war era and into the triumphant years of the space program in the 1960s. It’s a history that Shetterly tells with skill and obvious passion, placing these women at the center of the narrative “not just because they are black, or because they are women, but because they are part of the American epic.”

Hidden Figures is the 2019 Nashville Reads selection. Shetterly answered questions from Chapter 16 by email.

Chapter 16: You grew up among the black scientists and engineers of Langley, and your father worked with Katherine Johnson, so you were already familiar with the world of Hidden Figures. Did your research uncover anything that challenged your assumptions?

Margot Lee Shetterly: The absolute numbers of women doing this work surprised me. This isn’t a story about a handful of women. There were scores of black women, hundreds of women from all backgrounds.

Chapter 16: The women of West Computing were brilliant and ambitious, but I was struck by how much family, community, and collegial support enabled their careers. How important was having a network of support to these women? What can brilliant, ambitious women today learn from these women?

Shetterly: The women relied on their extended families to help them manage their lives. They wouldn’t have been able to do it without that support. Grandparents, aunts and uncles, neighbors, churches, and community organizations formed a strong social fabric that helped them to raise their children even as they maintained demanding jobs. Their activities outside of work provide meaning, belonging, and identity. The extended network was an essential part of their lives.

Chapter 16: In the book’s epilogue, you describe it as a story about “the triumph of meritocracy,” and it certainly is, but it’s also an emotionally rich human story. On a personal level, what was it about these women’s lives that touched you most deeply?

Chapter 16: In the book’s epilogue, you describe it as a story about “the triumph of meritocracy,” and it certainly is, but it’s also an emotionally rich human story. On a personal level, what was it about these women’s lives that touched you most deeply?

Shetterly: They were simultaneously committed to their families and communities and passionate about their work. They managed to accommodate a variety of roles and identities in their lives.

Chapter 16: The story of Katherine Johnson and John Glenn is inspiring, but Dorothy Vaughan’s quieter, more bittersweet story seems just as meaningful and important. Did you struggle with finding a balance in the narrative between the more dramatic moments and the smaller, less stirring aspects of the history?

Shetterly: Absolutely. The big moments are captivating, but the small victories and conflicts are the ones that most of us live day in and day out—harder to write, perhaps, but equally resonant. One of my great regrets is that Dorothy Vaughan didn’t live to see us celebrate her achievements in this way.

Chapter 16: The film was criticized for taking some liberties with the facts, but you’ve said you’re happy overall with the adaptation. Can you talk about your expectations for the film versus your commitment to historical accuracy in the book?

Shetterly: What pleased me about the film is that even though the adaptation required changing some of the historical facts, it hewed very closely to the truth of the story and the history. I think that the recognition of that truth is why people from all backgrounds have responded so strongly to the movie.

Chapter 16: One thing history provides is a richer perspective on our own time. What do you think the story of Hidden Figures can say to us about the present moment?

Shetterly: For every famous face or a memorable event, there are any number of unknown people behind the scenes supporting the person, or responsible for the event. True in the past, true today. The headlines are just the beginning of a more interesting story.

Chapter 16: What advice would you give to a writer who, like you, is not trained as a historian but finds a compelling piece of history that begs to be told?

Shetterly: Follow your curiosity wherever it leads, and eventually you will have your book.

Maria Browning is a fifth-generation Tennessean who grew up in Erin and Nashville. Her work has appeared in Guernica, Still, Hippocampus, and The Los Angeles Review of Books. She’s the managing editor of Chapter 16. p>