Soulful Dudes

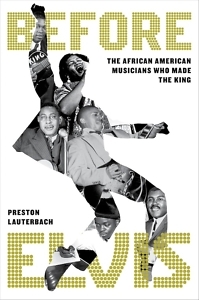

Preston Lauterbach chronicles the Black pioneers who created Elvis Presley’s music and style

In the 1990 hip-hop anthem “Fight the Power,” Chuck D of Public Enemy slammed Elvis Presley. Elvis may have been “a hero to most,” but for the militantly conscious rapper, that “sucker” was a “straight-up racist,” lumped with the conservative icon John Wayne.

The lyrics evoked the long, complicated debate over Presley’s legacy: Did his music bridge a racial chasm, or did he steal from Black artists? In Before Elvis, Preston Lauterbach flips the frame on this question. He explores Elvis through the lives of the Black musicians who shaped his style.

Lauterbach is the acclaimed author of books that explore the history of Black music and Black Memphis, including The Chitlin’ Circuit and the Road to Rock ‘n’ Roll, Beale Street Dynasty, and Bluff City. He answered questions via email from Chapter 16:

Chapter 16: Is Before Elvis shaped by your earlier books on music and Memphis? What compelled you to write the book, and how did the project evolve?

Preston Lauterbach: Before Elvis is both a return to my beginning and a culmination of what’s happened since. My love of music and my knowledge of Black artists came from being an Elvis fan as a kid. Hearing his versions of “That’s All Right” and “Mystery Train” and reading about the histories of those songs from Peter Guralnick’s liner notes led me to the Black originators. I followed those stories back to the larger worlds that I eventually explored in books like The Chitlin’ Circuit and Beale Street Dynasty. In a bigger sense, those songs and their stories helped me understand the importance of Black culture to American culture and the need to set the record straight. Before Elvis clicked when I saw the Elvis biopic and read that critics and fans wanted to know about Elvis’ relationship with Black culture and Black artists. I thought I could do that.

Chapter 16: Elvis aficionados know that Presley’s breakout song “That’s All Right” was written and performed by Arthur Crudup and that his hit “Hound Dog” was first done by Big Mama Thornton. If we focus on these Black musicians, what can we learn about the rise of rock ‘n’ roll?

Lauterbach: Of course those songs are foundations of rock, but by the time of the American mainstream rock ’n’ roll craze of 1956, Crudup and Thornton had become so marginalized and disillusioned, they practically gave up music. So as it often happens in American business, the inventor ends up with a knife in their back and their money in someone else’s pocket. But both of those artists eventually found a niche white audience thanks to the interest in rock’s roots that came about during the 1960s. In fact, the two of them, along with Little Junior Parker, the originator of the Elvis classic “Mystery Train,” performed at the Ann Arbor Blues Festival, I think in 1969. I would give a digit to have been a fly on the wall at the card game backstage that night.

Chapter 16: “The most overlooked, underappreciated, and important Elvis Presley influence,” you write, “was a man named Calvin Newborn.” How did you come to this conclusion?

Lauterbach: Most of the book is devoted to the people who wrote and recorded Elvis’ biggest songs, but that’s only part of the story. I think that Elvis’ stage presence is as important to his legacy as his songs are, and as with many of his most important songs, there’s a Black originator behind the curtain. Elvis’ first recordings hit radio in 1954. But he didn’t become a superstar until 1956. That happened after people saw him on television. To this day, his moves, the gyrating hips, his “Elvis the Pelvis” identity, are such a powerful aspect of his fame and his mystique.

Lauterbach: Most of the book is devoted to the people who wrote and recorded Elvis’ biggest songs, but that’s only part of the story. I think that Elvis’ stage presence is as important to his legacy as his songs are, and as with many of his most important songs, there’s a Black originator behind the curtain. Elvis’ first recordings hit radio in 1954. But he didn’t become a superstar until 1956. That happened after people saw him on television. To this day, his moves, the gyrating hips, his “Elvis the Pelvis” identity, are such a powerful aspect of his fame and his mystique.

Elvis’ most important stage influence was Calvin Newborn, a performer young Elvis saw in Beale Street and West Memphis nightclubs. I had the opportunity to get to know Calvin. His insights add so much to the Elvis story. A lot of witnesses who were there maintain that Elvis took his whole presentation straight from what Calvin was doing at the Flamingo Room in Memphis right at the time Elvis cut his first sides at Sun Records. Calvin was philosophical about the whole thing. Calvin had a right to feel ripped off but shared a much more nuanced view of what happened with Elvis and Black culture, one that I hope readers will benefit from, as I have. My favorite Calvin quote about Elvis is, “He ate pork chop and gravy sandwiches. He was a soulful dude.”

Chapter 16: Did these Black artists ever benefit from Presley’s superstardom? Did they achieve cultural appreciation or financial success?

Lauterbach: The originators never benefited to the degree that they deserved to with respect to Elvis. But Crudup and Big Mama Thornton, in a very gritty way, used their stories to their advantage, telling their audience about what had happened and gaining appreciation. After Crudup died poor, as he knew he would, his family members fought for their rights and I think that readers will appreciate how that turned out.

Chapter 16: How, in the end, should we judge Elvis Presley? Is he celebrating Black music or exploiting it?

Lauterbach: People want one answer about Elvis and race, but as with other issues involving human beings, things developed as he changed over time. The Elvis who ate pork chop sandwiches with Calvin Newborn and sang at East Trigg Missionary Baptist Church in 1953 no longer existed in 1970. That young Elvis, according to multiple sources who knew him, stood out as a rebel against the Southern white order. His actions, many of which are historically documented, prove that he stood against segregation. He loved Black music, and he treated Black people with respect and courtesy.

Later in his superstardom phase, he could have done more for Black music. Many major touring rock acts on the road during the early 1970s had roots artists open for them and gained exposure for these artists. An Elvis roots show featuring Crudup, Thornton, Junior Parker, Joe Turner, and others would have been monumental. Even lacking that direct acknowledgment, artists like James Brown and Rufus Thomas, whose “Tiger Man” Elvis performed into the 1970s, maintain that Elvis functioned as a major ally, opening the door for Black culture to the mainstream. I’m not here to argue with James Brown about Black music.

Aram Goudsouzian is the Bizot Family Professor of History at the University of Memphis. His most recent book is The Men and the Moment: The Election of 1968 and the Rise of Partisan Politics in America.