The Crafts of Freedom

Martin Luther King Jr.’s Mountaintop speech was more than brilliant rhetorical art; it was also the culmination of a lifetime spent in intense and extensive reading

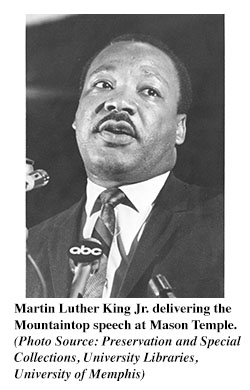

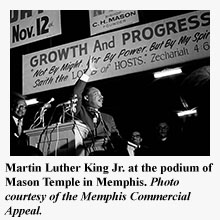

On April 3, 1968, Martin Luther King Jr. was summoned to the Bishop Mason Temple in Memphis to address the striking sanitation workers and their supporters. King wasn’t scheduled to speak at the rally, but Reverend Ralph Abernathy, sensing the crowd’s disappointment, had persuaded King to come from the Lorraine Hotel to make a few remarks. Poor pay, unjust working conditions, and two tragic deaths  had led to the strike, now nearly two months long. Just the week before, protestors and police had clashed violently, leading to a court order against another march. King’s authority was being challenged among factions within the civil-rights movement, and it wasn’t clear that his insistence on nonviolent resistance would hold. The way forward was uncertain.

had led to the strike, now nearly two months long. Just the week before, protestors and police had clashed violently, leading to a court order against another march. King’s authority was being challenged among factions within the civil-rights movement, and it wasn’t clear that his insistence on nonviolent resistance would hold. The way forward was uncertain.

But by the end of his extemporaneous speech, King had come to the top of the mountain: “I’ve been to the mountaintop. … Like anybody, I would like to live a long life. Longevity has its place. But I’m not concerned about that now. I just want to do God’s will. And He’s allowed me to go up to the mountain. And I’ve looked over, and I’ve seen the Promised Land. I may not get there with you. But I want you to know tonight, that we, as a people, will get to the Promised Land! And so I’m happy tonight; I’m not worried about anything; I’m not fearing any man. Mine eyes have seen the glory of the coming of the Lord.”

King was killed the next day as he stood on the balcony of the Lorraine Motel.

Most of us are familiar with the Mountaintop speech. In the years since, King’s powerful closing words have gotten all the ink because his invocation of Exodus so eerily anticipates his assassination. His opening lines are equally brilliant: in them, King acknowledges that “[s]omething is happening in Memphis; something is happening in our world.” He imagines the Almighty offering him a “general and panoramic view of the whole of human history up to now,” and asking him, “Martin Luther King, which age would you like to live in?” King replies,

I would take my mental flight by Egypt and I would watch God’s children in their magnificent trek from the dark dungeons of Egypt through, or rather across, the Red Sea, through the wilderness on toward the promised land. And in spite of its magnificence, I wouldn’t stop there.

I would move on by Greece and take my mind to Mount Olympus. And I would see Plato, Aristotle, Socrates, Euripides, and Aristophanes assembled around the Parthenon. And I would watch them around the Parthenon as they discussed the great and eternal issues of reality. But I wouldn’t stop there.

As the speech unfolds—through the Roman Empire and the Renaissance and the Reformation and the Emancipation Proclamation and up to the New Deal—“I wouldn’t stop there” becomes a rhetorical refrain, building to a crescendo. At last, King tells the Almighty: “If you allow me to live just a few years in the second half of the twentieth century, I will be happy.” He admits that his own moment is bleak, that “the world is all messed up. The nation is sick. Trouble is in the land; confusion all around.” But even in the hatred and the contention all around him, King finds hope in his fellow demonstrators, in the cry for freedom across the globe: “Only when it is dark enough can you see the stars.” He’s making a defiant call for optimism in dire times.

Another way to consider the sweep of history in King’s Mountaintop speech is to remember that our own moment—the peak of our own mountaintop—is inevitably built upon the foundation of the past: no Egypt, no Memphis. No Athens, no Memphis. No Rome, no Florence, no Wittenberg, no Washington, D.C.—no Memphis. Wrestling with the past helps us appreciate how it has shaped our present.

Another way to consider the sweep of history in King’s Mountaintop speech is to remember that our own moment—the peak of our own mountaintop—is inevitably built upon the foundation of the past: no Egypt, no Memphis. No Athens, no Memphis. No Rome, no Florence, no Wittenberg, no Washington, D.C.—no Memphis. Wrestling with the past helps us appreciate how it has shaped our present.

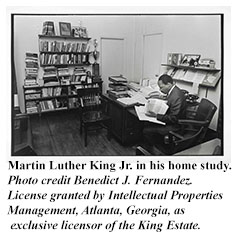

King pursued a demanding liberal-arts curriculum, first as an undergraduate at Morehouse College and later through his graduate work at Crozier Theological Seminary and Boston University. In There is a Balm in Gilead, biographer Lewis V. Baldwin notes that King’s undergraduate education included the study of Plato, Socrates, Kant, Machiavelli, Thoreau, Gandhi, and a host of other great thinkers—a study, Baldwin writes, that established “the foundation for his graduate work in philosophical theology.”

Little surprise, then, that King’s searing 1963 “Letter from Birmingham Jail” invokes (and extends) natural-law theory, citing figures such as Augustine, Aquinas, Luther, Bunyan, Jefferson, Lincoln, Buber, and Tillich. Or that his 1965 sermon at Temple Israel of Hollywood includes Plato, Kant, and Marx among generations of philosophers who “thought in terms of the promised land.” References to Shakespeare, Hegel, Tolstoy, and countless others permeate his oratory. King doesn’t allude to writers merely to name-check them; he was contributing to an ongoing cultural conversation, critiquing it even as he claimed it as his own.

For King, as for earlier African-American intellectuals, cultural history belongs to everyone. As James Baldwin put it in 1964: “My relationship, then, to the language of Shakespeare revealed itself as nothing less than my relationship to myself and my past.” Or, as W.E.B. Du Bois had earlier averred: “I sit with Shakespeare, and he winces not. Across the color line I move arm in arm with Balzac and Dumas. … I summon Aristotle and Aurelius and what soul I will, and they come all graciously with no scorn nor condescension.” In fact, Du Bois concludes with his own allusion to Moses: “Are you so afraid lest peering from this high Pisgah … we sight the Promised Land?” In his Mountaintop speech, King is participating in a cosmopolitan heritage that belongs to all of us.

We rightly associate Martin Luther King’s oratorical eloquence with his vocation as a Baptist minister, following his father and grandfather before him. But King also emerged from the rhetorical tradition of the liberal arts, transforming the sources with which he engaged throughout his too-brief life. Nowadays we tend to think of rhetoric as a pejorative term: calling a political speech “mere rhetoric” is a way to dismiss empty promises. Yet a long rhetorical tradition prevailed in the liberal arts until only recently. Rhetoric was designed to be a productive art: a necessary, high-level skill in persuading a public audience, drawing upon a treasury of existing knowledge.

We rightly associate Martin Luther King’s oratorical eloquence with his vocation as a Baptist minister, following his father and grandfather before him. But King also emerged from the rhetorical tradition of the liberal arts, transforming the sources with which he engaged throughout his too-brief life. Nowadays we tend to think of rhetoric as a pejorative term: calling a political speech “mere rhetoric” is a way to dismiss empty promises. Yet a long rhetorical tradition prevailed in the liberal arts until only recently. Rhetoric was designed to be a productive art: a necessary, high-level skill in persuading a public audience, drawing upon a treasury of existing knowledge.

King didn’t create the structure of his Mountaintop speech from scratch; he crafted it from rhetorical strategies that he had internalized through lifelong study. Both his education and the way he employed it are ample evidence that reading widely provides us with the resources for future thought, future speech.

Today both “liberal” and “arts” have narrow connotations that don’t adequately convey the ambitions of the traditional liberal-arts program of study. The emancipatory liberal arts were crafts of freedom: mental skills suitable to a free citizen. They were distinguished from the manual skills needed by uneducated and enslaved people—hence the continued tensions between “liberal” and “vocational” ideals that have bedeviled formal education since its origin.

As an undergraduate at Morehouse, King was already meditating upon these tensions, observing in a campus newspaper that “education has a two-fold function to perform in the life of man and in society: the one is utility and the other is culture.” He goes on to articulate an argument for an immersion in the liberal arts:

To think incisively and to think for one’s self is very difficult. We are prone to let our mental life become invaded by legions of half truths, prejudices, and propaganda. At this point, I often wonder whether or not education is fulfilling its purpose. A great majority of the so-called educated people do not think logically and scientifically. Even the press, the classroom, the platform, and the pulpit in many instances do not give us objective and unbiased truths. To save man from the morass of propaganda, in my opinion, is one of the chief aims of education. Education must enable one to sift and weigh evidence, to discern the true from the false, the real from the unreal, and the facts from the fiction.

The function of education, therefore, is to teach one to think intensively and to think critically. But education which stops with efficiency may prove the greatest menace to society. … We must remember that intelligence is not enough. Intelligence plus character—that is the goal of true education. The complete education gives one not only power of concentration, but worthy objectives upon which to concentrate.

King’s speeches insistently remind us that freedom is everyone’s birthright. Here he also chides us to remember that intellectual freedom—“thinking for one’s self”—involves continual labor: it’s something that we must learn, develop, hone, and practice. Alexis de Tocqueville called this arduous practice “the apprenticeship of liberty”. In other words, freedom entails activity; it’s a craft.

As we observe the anniversary of Martin Luther King Jr.’s death, it’s crucial to recall that this craft emerges through an ongoing dialogue with past thinkers – in King’s resonant phrase, “going forward by going backward”. We may never fully reach King’s promised land: universal education that inculcates good character and teaches us to discern the true from the false. But his vision should nevertheless be what guides us as educators and students, lawmakers and citizens.

[This article originally appeared on April 2, 2015.]

Copyright (c) 2015 by Scott Newstok. All rights reserved. Scott Newstok directs the Pearce Shakespeare Endowment at Rhodes College. This essay has been expanded in his book How to Think like Shakespeare (Princeton, 2020).