When Brotherhood Isn’t

Barry Moser’s memoir about growing up in Chattanooga tackles hard questions of race and family

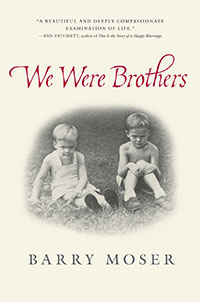

On the first page of his new memoir about growing up with his brother in postwar Chattanooga, the artist Barry Moser makes it clear that this won’t be the usual story of a Southern boyhood, full of swimming holes and fishing poles: “Without opportunity to be otherwise,” he writes, “Tommy and I were racists.”

Racism haunts We Were Brothers like a horror-movie killer, popping up when the reader least expects it. Just after a story about how his father built a fortune as an itinerant gambler, Moser turns the narrative to his mother’s best friend from childhood, a black woman named Verneta. One day when they are still quite young, Verneta and his mother, Billie, are playing in the back of a grocery store owned by Mosher’s grandfather. Billie’s two older sisters come in and ask if she wants to go to the movies. When Verneta says she wanted to go too, one of the sisters says, “Don’t you go bein’ silly now. You know you caint go.” Verneta starts to cry, runs to a bin of flour, and sticks her face in it. Then she runs back, grabs Billie’s hand, and says “Now can I go? Now can I go?”

Racism haunts We Were Brothers like a horror-movie killer, popping up when the reader least expects it. Just after a story about how his father built a fortune as an itinerant gambler, Moser turns the narrative to his mother’s best friend from childhood, a black woman named Verneta. One day when they are still quite young, Verneta and his mother, Billie, are playing in the back of a grocery store owned by Mosher’s grandfather. Billie’s two older sisters come in and ask if she wants to go to the movies. When Verneta says she wanted to go too, one of the sisters says, “Don’t you go bein’ silly now. You know you caint go.” Verneta starts to cry, runs to a bin of flour, and sticks her face in it. Then she runs back, grabs Billie’s hand, and says “Now can I go? Now can I go?”

As Moser tells it, Billie holds her friend, and they both weep. But years later, when Moser and his brother start playing with a young black boy, also named Tommy, Billie will let the child into their backyard but not into the house. And the sins of the mother’s racism are duly visited on the sons: to clarify which Tommy was which, the Moser brothers call their friend “Nigger Tommy.”

These are painful stories, all the more so because they fall so rarely in the book. Much of Moser’s memoir does in fact revolve around the average life of an average middle-class white boy in the 1950s South: learning to fish, building model airplanes, getting picked on by older boys. Moser is trying for something subtle but important. His book is not an examination of racism or Jim Crow per se—there are no lynchings, and the Klan makes just a walk-on appearance. It is, instead, an examination of how much a white boy in the Jim Crow South might have experienced of race, and racism.

For Moser, growing up in a world structured by white privilege, the answer is not much at all. Despite living in a relatively integrated neighborhood, he rarely interacts in youth with blacks, aside from intimate family friends like Verneta. And when he does, it’s with an air of absolute superiority, a faith that whites may treat blacks however they want, and that everyone, in both races, is OK with that. The only ones who aren’t are the Klanmen, who want to push blacks even further down the ladder—but who also, more importantly in retrospect, give license to people like the Mosers to feel like they are, somehow, racial moderates.

Moser packs a lot into this slim volume. Alongside race, he also examines brotherhood, in particular his own. And here, again, Moser goes against the conventional narrative: “When I read novels and stories or see films in which brothers are close and go places and have adventures, I often weep,” he writes. “I wish my brother and I had been buddies, but we weren’t.”

Moser packs a lot into this slim volume. Alongside race, he also examines brotherhood, in particular his own. And here, again, Moser goes against the conventional narrative: “When I read novels and stories or see films in which brothers are close and go places and have adventures, I often weep,” he writes. “I wish my brother and I had been buddies, but we weren’t.”

That the two are different people is obvious from early on. Tommy is athletic, a natural outdoorsman, a stickler for neatness, and an indifferent student; Barry is messy, artistic, and scholarly. They fight, like all brothers, but afterward they don’t make up—there’s no hugging it out; instead there’s only a resettling into an icy détente.

Moser tries to come up with an answer for why their relationship plays out this way, but the painful truth is that there isn’t one. Brothers don’t choose each other, and there’s no reason why they have to be friends. The world is awash in stories of brotherly love and brotherly hate, but the reality is more often brotherly indifference. You live together, and once you leave the house you drift away from each other, calling occasionally, if at all.

These two themes—race and brotherhood—come together as the Mosers move apart. Barry goes to college and then heads north; he sympathizes with the civil-rights movement and comes to regret his childhood racism. Tommy drops out of high school, joins the Army, and eventually gets a job with a bank. But he holds tightly to his racist views, a fact that divides the brothers for decades.

The last section of the book consists primarily of three letters—two from Barry; one, in between, from Tommy—that the brothers exchanged a few years before Tommy’s death, in the aftermath of a vicious fight about Tommy’s attitude toward blacks. In his first letter, Barry is accusatory, critical, righteous, and condescending; Tommy’s response is sprawling and defensive. By the third letter, Barry is forgiving and almost pleads for forgiveness in return—forgiveness for never quite understanding his brother, for never quite caring enough to see the world from his vantage point, the way a brother should.

Moser is searching for something that isn’t there, an answer to his own life’s questions—Who am I? Where did I come from? What do I believe?—in a place where many people are able to find it: in brotherhood. But, contrary to the title, Barry and Tommy are never truly brothers, despite being siblings. And Barry is left, alone, without the answers.

Nashville native Clay Risen is the author of A Nation on Fire: America in the Wake of the King Assassination and American Whiskey, Bourbon and Rye: A Guide to the Nation’s Favorite Spirit. His new book, The Bill of the Century: The Epic Battle for the Civil Rights Act, appeared in spring 2014. He lives in New York, where he is an editor at The New York Times.