Indomitable Spirit

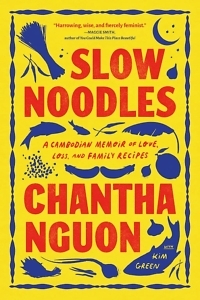

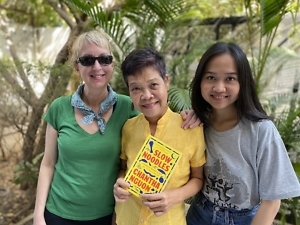

Chapter 16 talks with Chantha Nguon, Clara Kim, and Kim Green about the story behind Nguon’s remarkable memoir, Slow Noodles

Chantha Nguon’s Slow Noodles, released this month in paperback, has been lauded by foodies and book lovers all over the world, landing on Best of 2024 lists by publications like Food & Wine, BookPage, and Elle. This captivating memoir celebrates Nguon’s indomitable spirit as she chronicles her life growing up in Cambodia and her family’s terror-filled years fleeing to Vietnam to escape persecution under Lon Nol, before Year Zero and the terror of the Khmer Rouge.

She describes their time in a refugee camp, the atrocities she witnessed, and the deprivations faced at every stage. But she also describes the delicious food made by her mother and her sister, and later, by her. Through these stories, and the recipes that accompany them, she invites readers to understand Cambodian culture through both the pain of the past and the delicious flavors that sustained their hope for the future.

Snow had just begun falling in Tennessee where co-author Kim Green and I were joined on a video call by author Chantha Nguon in Cambodia and Nguon’s daughter Clara Kim in London. Our conversation has been edited for length and clarity.

Chapter 16: Thank you for agreeing to gather from these many corners of the world and to talk about the process and the imagination behind Slow Noodles. With the paperback coming out, and especially after receiving quite a number of end-of-year accolades, I’m sure you have been thrilled. I’m glad that we get to revisit it today and bring even more readers to your amazing story, Chantha. Why don’t we start by backing up to this project getting started? How did it all begin, and Kim, how did you get connected?

Kim Green: Chantha and I met in 2011. I was doing a magazine story for a now defunct women’s magazine called Her Nashville, and that story was about the partnership between Chantha and [Nashvillian] Ann Walling, about the Mekong Blue silk and the Stung Treng Women’s Development Center (SWDC). Walling was a donor whose family foundation provided the funding that helped start the center. After the story came out, Ann Walling called me and said, “Would you like to do a book project?”

So in early 2012, Chantha and I started speaking by email, and she would send me parts of her life story, and I didn’t quite grasp at the time how difficult that process was for her. She would sit down to answer questions by email, and it was very painful. Later that year, I went to Cambodia for the first time. It was October of 2012, and we spent two weeks getting to know each other and discussing the project — whether to do the project, how to do the project. And through those conversations we settled on the idea of telling her stories through her artistry in the kitchen, her food memories, her family recipes from her mother and sister.

Chapter 16: Chantha, how did you and Ann first consider the idea of a book?

Chantha Nguon: For more than 10 years, Ann Walling just trusted us to do whatever we believe is good for our community, so I feel like I’m in debt to Ann because of her trust. Every time she invited me over, she invited me and my children over, and every time [something] reminds me of my life, I would just say it — and finally she said she wants my story written into a book. And I said no, it’s too difficult for me. I choose the part I want to tell. But I don’t want to live with my past again. That’s too painful for me. Then she convinced me over about two years, and finally I said, I owe her big, and I have nothing valuable to pay back her love and her trust and her support. She wanted my story, and I think that’s the only valuable thing that I can give back in return for her love. So I agreed, and that’s how she introduced Kim to me.

Chapter 16: That’s beautiful. And the world is better for your feeling that you could share this story. Kim, when you first went to Cambodia, the book wasn’t a guarantee. When did that trust first come between the two of you? When did it become clear, Kim, that you could carry this story, and Chantha, when did it feel like that would be okay?

Chantha Nguon: For me to tell the story is the job I hated most in my life. If I have a choice, I wouldn’t take this job. So I have to say I don’t have a choice; [this] is a very difficult job that I have to carry on. And I work with Kim, because I trust Ann, and Ann trusts Kim. I didn’t have any doubts about Kim at all. But it’s really difficult for me to answer the questions by email or to work with Kim. And it’s also very difficult for Kim to understand why I was so angry and crying so much. I don’t know if Kim had any experience with writing a story with people living with trauma. So that situation was very difficult for both of us, but we did it anyway.

Kim Green: Yeah, that’s so true. I have interviewed people who’ve been through all sorts of things, but never a life story like hers, and as I got to know her better, as I saw how difficult it was for her to tell these stories, I really worried about it. I really worried about the human decency and ethics of asking her to do this. I still wanted her permission, so I would ask not just, “Is this whole project okay?” but “Is what we’re doing today okay? Is what we’re going to do tomorrow okay? Is this conversation okay?” And I learned, over time, when to gently press and ask for the whole story, when to step back and take a break. I’m not convinced I did any of that right. I just did my best and worried about her and fell in love with her and cared about the right way to do things.

And like she said, sometimes the stories just come out, and it’s usually when she’s cooking or when we’re having a meal. I could see that she transforms almost into a different person when she’s cooking. She’s brilliant in many ways, but her cooking is next level. And so I just thought since food is how the stories came out naturally between us, maybe it could happen the same way on the page, and maybe it could also become not just a story of loss and sorrow, but that it could become a celebration of her family, her memories, her artistry, her mother, her sister.

Chapter 16: It really comes through in the book, the idea that sharing stories around a table is how community is built, where intimacies are formed. You’ve invited all of these readers to sit with you or to cook with you, and to hear your voice coming through in every piece of this story proves that you accomplished exactly what you set out to do, difficult though it was for the both of you. With Slow Noodles, you’re bringing Cambodian food to so many people around so many tables. How has it been having this book celebrated in those food worlds?

Clara Kim: My mom loves cooking for people, and I think she shows love through food. I remember when we did the pop-up in Nashville, and we had so many in the Asian community in Tennessee who came. We were all in the kitchen, cleaning up. It was just a room full of strangers, and they were all Asian Americans, and they loved the food, and it felt like home because everyone was sharing and talking and asking questions and being really grateful for the story, and then everyone left with a box of leftover food to take home, which is what happens when you go to your family’s house. They felt like family even though they were all strangers.

Clara Kim: My mom loves cooking for people, and I think she shows love through food. I remember when we did the pop-up in Nashville, and we had so many in the Asian community in Tennessee who came. We were all in the kitchen, cleaning up. It was just a room full of strangers, and they were all Asian Americans, and they loved the food, and it felt like home because everyone was sharing and talking and asking questions and being really grateful for the story, and then everyone left with a box of leftover food to take home, which is what happens when you go to your family’s house. They felt like family even though they were all strangers.

They came there for my mom and for the story, and I think in Nashville, there aren’t a lot of spaces for the Asian community to come together in that way. And I could see my mom’s perspective about that evening and her book — what it does for the community. I could see it change. I think it was like a light bulb going on as she realized how important the book is for that community. When I left home, I felt the same. I feel like a lot of people didn’t know about Cambodian food, so I learned all the recipes, and I cooked for my friends and strangers and people I know, and there’s a sense of pride to be able to share it with other people. I love talking about it. I love sharing all those stories as well.

Kim Green: Back in the kitchen after the pop-up is one of my favorite moments ever. Everyone just surrounded your mom with admiration and love, and I remember some of them saying things like, “We come from refugee families, and we wanted to hear these stories from our own parents, but they didn’t want to tell us, or it’s too late now. And so you told your story, and in a way, it’s for all of us.” And I thought, if it was even my right to want anything from the book, that is what I wanted. I wanted a moment like that. That moment of connection between Chantha and other people from refugee families with parallel stories, who could connect her story with their own family history. And it absolutely happened. And it was really, really beautiful that night.

I think it’s happening all over the place now, just quietly. We got to see it ourselves that day. But you know, on Instagram I see people posting Here’s our Asian American book club, reading Slow Noodles and having a dinner party, and so they get to then try the food and tell stories and share their family histories as they read about Chantha’s. And that’s absolutely lovely. There are also a few Cambodian restaurants, two or three female Cambodian American chefs who are making a name for themselves in San Francisco and Chicago and New York. So there’s momentum building with the book and the restaurants and those chefs, and they’re inspired by each other, I think. Cambodian food is gonna have its moment soon!

Chapter 16: Maybe it’s just a coincidence that those chefs are women, but there’s so much in Chantha’s life story about women supporting other women and building structures to make opportunities possible for women. But the work that Chantha describes with her mother and her sister making all this amazing food, and it just was what women did. It wasn’t considered special. We read, Chantha, of your sister working for so many hours through the night to make tofu to sell in the market, and we think what an incredible act of service — none of us would do that! And you think, well, that’s just what we did. And so I’m curious if maybe there’s a connection there — that your book allows these women to be seen and for their contributions to food culture to be valued and respected and elevated. Could that be true?

Chantha Nguon: Well, the oldest daughter in the family, it’s a duty for her to do everything all day. So I think that’s why I raised my daughter out of that cultural norm where the girl has to be a slave of the family. Even if the girl goes to work, she has to give all of her salary back into the family to support the parents, to support the younger brothers. So that’s the culture I’m living in and I was born in, and my sister is the symbol of the culture. I look at it even for myself – I am working, and I am working more than my husband, but it’s me who puts food on the table every time, every meal for my husband and my children, but for me I’m proud. I’m proud to work a lot more than my husband, but I don’t want my daughter growing up in that culture. So that’s why she’s there.

Kim Green: Also part of your life’s work at SWDC, it strikes me, has been to help women find another way besides being stuck in those cultural traps.

Chantha Nguon: Yes, because the women we are working with, they are illiterate. So it’s a way to be financially independent. It’s not what they can see or they can plan by themselves. So again, I look at myself. I’m financially independent. If I don’t want to cook for my husband, I pay someone else to cook. I’m free to spend my money, and that’s how I use it. I adopt it into SWDC to help women be financially independent. Independence equals freedom, and they have freedom, those women.

Chapter 16: Well, I hope to someday see a Cambodian restaurant helmed by a woman chef in my region, and I can go and enjoy and think, Chantha, you did this! But until then, the book does have recipes, and they aren’t so complicated or terrifying as to make them off limits to your average reader. That said, many of your readers aren’t going to be familiar with the slow, thoughtful techniques that you encourage us to use, or some of the ingredients might be new. So if I could only make one recipe from the book, which one would it be?

Chantha Nguon: It’s the simplest, but everybody I cooked for enjoyed it — the S’gnao Chruok or Chicken Soup the Village Way. I still remember when I was 6 or 7 years old, and that’s the first time my parents and my sister took me to the picnic at their friend’s farm, where I ate this soup. I asked my sister, “What is in here that is different from what you cook at home?” And so she told me, and ever since then, I cook it the same way. I still remember the taste, and I still remember the feeling: How good! And then Kim came to meet me the first time about the project, and I was working in the remote area. No electricity. They cooked that dish, and I saw Kim, I just watched her enjoy the soup. It’s the simplest way of cooking: just boil the chicken and make a soup — that’s the chicken soup village style.

Kim Green: I mean, we’ve all had chicken soup, right? You just add some, add some lemongrass and a squeeze of lime and some fresh herbs, and —

Chantha Nguon: Lime leaf, lime leaf.

Kim Green: Right, lime leaf. And so it’s really familiar with a few extra tastes that you might not usually put into chicken soup. But the first thing that Clara taught me to make was the stir-fried noodles. For me, that would be dish number one.

Clara Kim: That’s the first thing I learned how to make.

Chapter 16: How old were you when you learned how to make that dish?

Clara Kim: Oh, I was 18. I left for college in the US, and I missed home food. I’ve always helped my mom in the kitchen, and I’ve made food at home, but it was very simple. I was mostly the sous chef. I never really cooked for myself until I went to college. And it was the simplest and easiest dish to learn if you haven’t made Cambodian food before. I think everyone I’ve made it for loved it. But my favorite dish from the book that represents Cambodian flavors really well is Num Banh. It’s from the north of Cambodia, where my mom is from, and it’s a light fish curry with coconut milk, and you serve it with rice noodles and herbs and vegetables. And a bit of chili flakes, and it is delicious. I make it all the time for my friends.

Chapter 16: Like a lot of people, I’ve embraced cooking at home more in the last handful of years, especially stretching outside of my Southern roots. The meals that got passed down to my mother, and then from my mother to me, did not ever include coconut milk. But my daughter and my son will receive recipes from me that do because I love it. It’s so delicious. It is amazing how cultural traditions will pass through generations, and that with each generation they will change, they will be added to, and the culture itself will change and be added to as well. I’m very thankful that these recipes can be part of that for my family. Kim, have you always been someone who cooked? Or has this book changed your relationship with food as well?

Kim Green: I did not grow up cooking like Clara did. When I was her age, I had no culinary skills, and I also didn’t have great taste. But when [my partner] Hal and I got together, we got food-curious and started going to really good restaurants. We made friends with chefs, we traveled some, and so we developed our tastes and started to be more adventurous. And then, when Clara and Chantha came into my life, I definitely learned a lot more techniques, fell further in love with food, and got much more skilled. When you go to a dinner party hosted and cooked by Chantha, you definitely feel loved. Not only does she cook beautifully, but she’s watching everybody. She’s noticing who likes what, who goes back for seconds. And so if you attend another dinner party by her, she will know what your favorite dish is, and she’ll maybe even cook something different, specifically for you, based on what she saw you enjoying. And Clara has that skill, too. So it’s not just the skill of being able to cook delicious food, but when they throw a dinner party, it is an event full of love and artistry, and it’s an amazing experience.

Chapter 16: And you guys did that, didn’t you? Is that dinner party idea the foundation of the Slow Noodles Cooking Tour that happened in Nashville before the book came out?

Kim Green: That was 2018. Clara had graduated from Sewanee. Chantha came for her graduation, and so we were together all summer long. And we thought: Let’s start an Instagram feed. Let’s try to develop people’s taste in Cambodian food. Maybe get some fans. So we cooked for half the city, and lots of people came here to the house, and we went to other people’s houses, and Chantha told stories about the dishes, and then we demonstrated a little bit, and then we would serve a great big meal at the big table or out in the garden. And we were exhausted, but I think people had amazing experiences trying all these foods, and then they continued to follow us after that. So when the book came out, there were all these people who had met Chantha and who had tasted her food. And Clara and I got a lot of experience washing dishes and chopping vegetables.

Chapter 16: How many of those did you do that summer?

Kim Green: We must have served at least a hundred people.

Chapter 16: Oh, wow!

Clara Kim: Oh, yeah, we did. I think we went from people we knew to strangers we had never met.

Kim Green: And word spread. People shared their pictures and their videos on Instagram, and then other people wanted to be a part of it. And so by the end of the summer I was getting emails like, when’s the next one? I missed it. I think we could have continued filling up the kitchen.

Clara Kim: We would have been rich by now.

Chapter 16: People are hungry for that kind of community that can only be formed around a table. And to your point, Clara, when it is strangers, it can be even more powerful and more of what people are missing in today’s culture. We’re super connected digitally. That this call across four international time zones can even occur is an amazing advancement. But how much more incredible it would be if we were sitting together at a table having never met one another, and these stories started arriving.

Chantha Nguon: Yes, it’s amazing.

Chapter 16: Chantha, everything I read and hear tells me that people immediately feel that love. They see something in you that draws them closer. You are a connector, it seems to me. And you have done that now through this incredibly hard work that you were reluctant to take on.

Chantha Nguon: I hope so. Since the book came out, many people have come to me and opened up, so I hope everybody who has a past like me has the courage to tell their story. It’s really helpful because I was not like this before I worked with Kim. Only my daughter had seen how difficult my life was. It was just inside me and made me unable to look forward into my future. But from telling the story, I am able to let go of some of it. And I wish everybody who has a painful past should be able to let it out to help themselves.

Kim Green: There’s a podcast that invited Clara and Chantha as guests. It’s a Cambodian American woman and her father. It’s called Death in Cambodia, Life in America, and the whole point of the podcast is to spur these conversations between the generations, the survivor or Year Zero generation and their children, and maybe even grandchildren. What was that like, the conversation with Dorothy and her dad?

Chantha Nguon: She was helping him to tell the story. But she said from the beginning she was working in a university, and she took him out to talk to her class about his story, and at some point, he couldn’t, he couldn’t control it, and he went totally, uncontrollably angry. And that’s how we who are living with trauma, with what we’ve been through, that’s our life. Every small thing can trigger our fear, our anger. But after 60 episodes, she was able to help her father to finish his story. I’ve heard many different stories from the second and third generation. They told me I don’t know what to do because I wanted my parents to share, and my father started telling me everything, but then suddenly he stopped, and I couldn’t convince him to talk more. I understood it so well because that’s what my children used to live with. With parents with PTSD, it’s very difficult. It’s not just for us, but for the next generation as well.

Chapter 16: Clara, you have noted how hard it could be growing up. Every child wants their family to feel okay, and as a child you can’t fix these things. But it has to have helped to be part of this project, especially given that you got to record the audiobook. Was that difficult? Was it powerful?

Clara Kim: Yeah, I think the project itself has been healing for the both of us, because like my mom mentioned earlier, the stories I heard when I was younger, she chose to share specific parts of her life, and with the book, there were some really dark moments that I didn’t know before. And I think, just understanding her through the book, helped me understand who she is as a person and as a mother as well. Because I really didn’t understand that, and I don’t think I will fully ever be able to, but I think it helped bring the two of us closer together. There were a lot of moments of reflection and sharing about our feelings.

With the audio book, I really didn’t think too much of it at the beginning. I sent some audio samples to the editor and the producer, and they really liked it. So I spent the next week and a half, reading the book, word by word, out loud to myself, marking every sentence, every word that I didn’t know in French or Vietnamese and calling my mom and asking her how to say specific words, because my mom’s accent is very different than other Vietnamese accents. So I had to think about that as well. I knew certain sections of the book would be really difficult for me, and during the recording, I would warn the producer: Okay, this chapter is coming up. I’m gonna have to take a break. I have to breathe through this section a little bit. But I think the most interesting part was when I was reading about myself through my mom’s perspective. It felt a little bit strange, especially reading it out loud with people in the room like the audio tech person and the producer on the line. But it was a great experience for me, and I’m really glad I did it.

Kim Green: You did a beautiful job.

Clara Kim: Thank you.

Chapter 16: And thank you all for this conversation and for your beautiful book. Here’s to hoping that people continue to gather around tables and make this food and share their stories because of the work you have done.

Sara Beth West is a librarian and a freelance writer focusing on book reviews and author interviews. In addition to Chapter 16, publications include Kirkus, Shelf Awareness, BookPage, Southern Review of Books, and more. She lives in Chattanooga.